|

|

|

|

February 2013

|

The UWI Seismic Research Centre at 60: by Dr. Joan Latchman

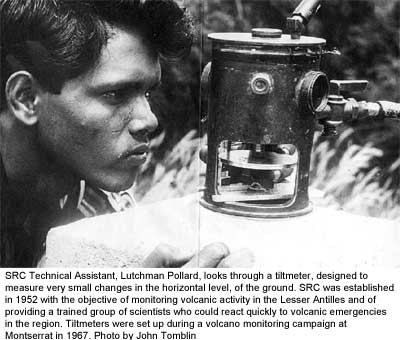

In 1993, as we prepared to mark our 40th Anniversary, we contacted Prof. Patrick Willmore, who was instrumental in establishing the original agency and he confirmed that a volcano-seismic episode, causing damage in St. Kitts-Nevis, in 1951-1952, led the British authorities to seek advice from Sir Gerald Lenox-Conyngham, who had supervised the study of a similar episode in Montserrat in the 1930s. He assigned one of his younger colleagues, Dr. Patrick Willmore, to investigate the activity. Prof. Willmore recalls that it was immediately obvious to him that the recommendations of the Montserrat study had been concentrated too strongly on Montserrat itself, when the history showed that these crises cropped up at different times from one end of the chain to the other. What was needed was a centre of scientific competence located in a place with good air communications to all the other islands. It should be noted that, at that time, the theory of Plate Tectonics, which provides a framework for the joint spatial occurrence of earthquakes and volcanic activity, was yet to be fully formulated.

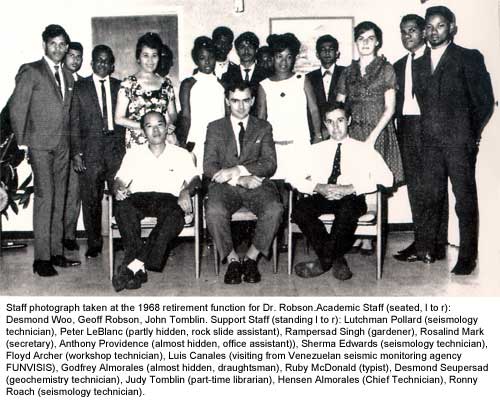

The operations of the Volcano Research Department were first set up under the regional Research Centre at the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture in Trinidad (forerunner to the St. Augustine Campus of the UWI) and supported by British Colonial Development and Welfare funds. Accommodation was initially provided in the Treasury Building on Marine Square (now Independence Square), Port of Spain, Trinidad, and later in Whitehall, Queen’s Park West, by the government. The first seismograph deployed in the new Eastern Caribbean network in the early 1950s was the Trinidad station, and it was initially installed in St. Clair, then moved to North Post Signal Station, at the head of the Diego Martin Valley, which, although a quieter site, was difficult to access. A location suitable for both office, and station would be the ideal solution, but the station remained there until August 1958, at which time it was moved to the Main Building at the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture in St. Augustine. In 1959, construction of a permanent home for seismo-volcanic studies, the Seismic Research Unit, at this site, commenced. The network began with three seismograph stations, with one located in each of the islands of Trinidad, St. Vincent and Dominica. This has grown to more than 60 stations throughout the countries of the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean. The early data acquisition system used a recorder to trace the ground movements on photographic paper that had to be chemically processed and dried before recordings could be analysed. For stations in other islands, the processing was done by a station operator, who mailed the records to Trinidad in bi-weekly or weekly batches. In 1962, the American World Wide Standardized Seismograph Network (WWSSN) station TRN was deployed in Trinidad, collocated with our own station. Through this involvement the Unit became more internationally recognised as it provided reliable, high quality data to the global seismic monitoring network. Building on this reputation, the first Earthquake Catalogue for the Eastern Caribbean covering the period 1530-1960 was assembled and published. With this growing reputation, the Unit was well poised on 29th July 1967, when the Caracas earthquake occurred, for Dr. Robson to be identified by UNESCO as the scientist to lead a reconnaissance mission to report on the destructive impact of that event.

By 1982, the Unit was developing data acquisition and processing systems – the Soufrière System – for use on its own in-house computers. These advances were funded by a grant under a UNDP project to enhance surveillance in St. Vincent following the earlier eruption of the Soufrière volcano. The digital data capability, made possible by the introduction of this system, completely changed the way location analysis was undertaken at the Unit, moving from pencils, rulers, magnifying glasses and paper charts and hand-cranked mechanical calculating machines to on-screen event inspection, and computer storage of earthquake readings. The pioneering development that ported this system onto a personal computer (then in its infancy) was such a significant development that other regional agencies chose to use it for their own data acquisition and processing needs. For several years it was being used in Venezuela, Puerto Rico and Jamaica; all reporting a high level of satisfaction. Although we are currently transitioning to a different seismic system that is being used widely around the world, in the interim, the WURSTMACHINE component of the Soufrière System continues to be the backbone of seismic data processing here at SRC.

The fact is that all the infrastructural development and significant population growth that have been taking place in the region can be very negatively affected by an earthquake of the size that that has not occurred for more than a century. Most give it a fleeting thought, usually when they feel a slight tremor. We know, however, and have always worked with the knowledge, that societal development can be set back a generation if measures are not put in place to ensure that our regional development plans factor in geological vulnerabilities. (At this time, exposure in Trinidad & Tobago is at over a trillion $TT of wealth – infrastructure and buildings – accumulated since 1981.) In the early 1980s the Unit became involved in the effort to develop a regional building code and expanded research that would provide the parameters needed for implementing such a code in practice. Several assessments on the seismic and volcanic hazard levels in individual islands across the Eastern Caribbean as a whole were published. In the mid-1980s, for example, a Volcanic Hazard Map for Montserrat was produced that well described the potential impact of activity at the Soufrière Hills Volcano, in the south of the island, as the subsequent, 1995 and ongoing activity there proved. A major advancement took place in this area with the Unit’s participation in a regional project (1989-1994) to develop seismic hazard maps for Latin America and the Caribbean. The first homogenous earthquake catalogue for the Caribbean region was compiled and hazard maps at a quarter degree resolution were produced, with the potential to prepare higher resolution maps at the sub-regional level. There is again an effort to develop a building code and the SRC is a member of that committee.

As we moved into the 21st Century, it became clear that there was a need for more effective communication of the vulnerability of the region to geological hazards and, so our activities expanded to include a dedicated Education and Outreach programme. The staff position was filled with a non-scientist, a communications specialist, to bridge the communication divide that exists between scientists and the general public. Most recently, when a geophysicist position became vacant, a decision was taken to fill it with a seismology-engineer to serve as the bridge to the engineering community, since many of the products of our scientific investigations are needed by the engineering community. Recent outputs that directly address the foundations of hazard preparedness are the Volcanic Hazards Atlas of the Lesser Antilles, updated Seismic Hazard Maps for the Eastern Caribbean Islands and Tsunami Smart promotion. It should be noted that keeping pace with state-of-the-art technology over the years, initiatives to improve public awareness and scientific thrusts do not and cannot come from our regular budget. The SRC is directly financed by the Governments of the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean and these contributions cover recurrent expenditure. All upgrades have come through staff initiatives, whether it is building equipment, rehabilitating old equipment or from collaborative projects and funding agencies.

However, that thread is becoming thinner and thinner and, in just over a decade, the SRC will be in the position of a having a cadre of staff with no clear connection to its origins. As it stands, the work of the SRC directly benefits the peoples of our region, not only episodically when there are geological crises, but routinely as we promote the necessary awareness for sustainable development. Within a University setting it would be very easy, with research in the title of our Centre, for the vital monitoring and observational role that the SRC undertakes to be neglected in favour of more esoteric, academic pursuits. We are doing all in our power to promote continuity and excellence in our basic services, as well as cultivating valuable research insights, so that the Seismic Research Centre continues to play an important role in the future development and resilience of our region. |

The countries bounding the Caribbean Basin were known to be vulnerable to devastating earthquakes from the time of the first European settlements, with accounts of such events first beginning to appear early in the 16th Century. All the territories in the region were colonies of one or other of the European colonising powers, which brought with them not only their languages and culture, but their architecture. Within the first few decades, the islands had been transformed into villages, towns and cities patterned after various European models, including the beautiful stone structures known there. The vulnerability of such structures to shaking by the large earthquakes that sometimes occurred in the region eventually became evident. The volcanic threat, on the other hand, was well known on the western side of the Caribbean Basin, but less so in the eastern island arc. Gradually the threat on this margin emerged, as several of the islands experienced episodic high level seismic activity associated with volcanic centres and then two catastrophic eruptions took place, in Martinique and St. Vincent, in 1902, claiming more than 30,000 lives.

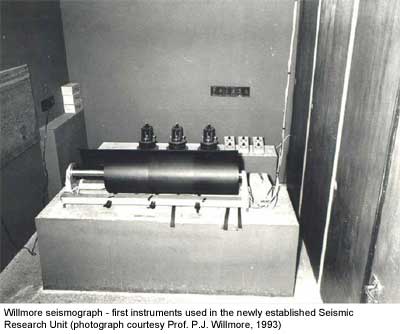

The countries bounding the Caribbean Basin were known to be vulnerable to devastating earthquakes from the time of the first European settlements, with accounts of such events first beginning to appear early in the 16th Century. All the territories in the region were colonies of one or other of the European colonising powers, which brought with them not only their languages and culture, but their architecture. Within the first few decades, the islands had been transformed into villages, towns and cities patterned after various European models, including the beautiful stone structures known there. The vulnerability of such structures to shaking by the large earthquakes that sometimes occurred in the region eventually became evident. The volcanic threat, on the other hand, was well known on the western side of the Caribbean Basin, but less so in the eastern island arc. Gradually the threat on this margin emerged, as several of the islands experienced episodic high level seismic activity associated with volcanic centres and then two catastrophic eruptions took place, in Martinique and St. Vincent, in 1902, claiming more than 30,000 lives. This recommendation became the Volcano Research Department, later renamed the Seismic Research Unit to reflect that earthquakes in general would be investigated. Then to more accurately reflect its status within The University of the West Indies (UWI) hierarchy, in 2008, ‘Unit’ was changed to ‘Centre’. The highlight of the 1993 activities was a conference and towards the end of the year, we shared the Conference Programme and Abstracts with Prof. Willmore, who at the time was recovering from illness. It was with clear pleasure that he wrote saying that the conference was all that he could hope for in showing how the seeds sown by him and Dr. Geoffrey Robson, who was appointed to execute the vision and became the first Head of the Seismic Research Unit, had found such fertile ground at St. Augustine and had grown into a full-scale regional organisation. Although his mark on the wider seismological world is undeniable, for many years his Willmore seismographs were used in recording earthquakes in our region and he derived tremendous satisfaction from learning of the continued development of our agency as part of the legacy of his work.

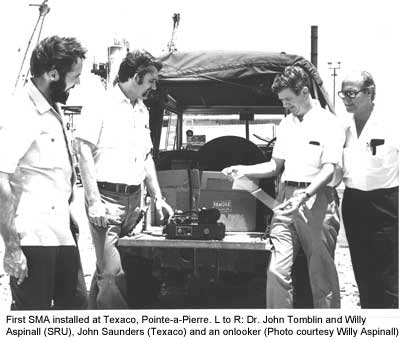

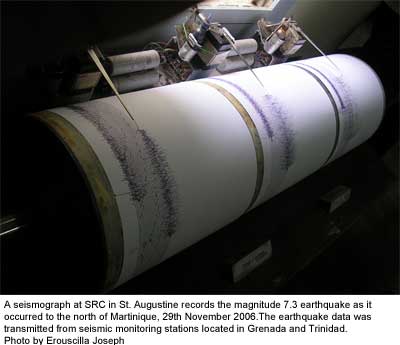

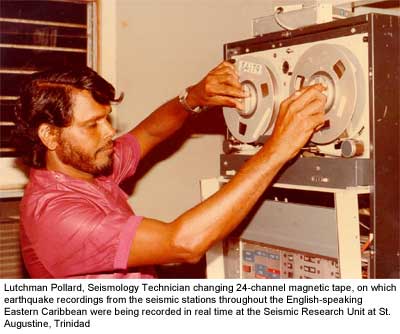

This recommendation became the Volcano Research Department, later renamed the Seismic Research Unit to reflect that earthquakes in general would be investigated. Then to more accurately reflect its status within The University of the West Indies (UWI) hierarchy, in 2008, ‘Unit’ was changed to ‘Centre’. The highlight of the 1993 activities was a conference and towards the end of the year, we shared the Conference Programme and Abstracts with Prof. Willmore, who at the time was recovering from illness. It was with clear pleasure that he wrote saying that the conference was all that he could hope for in showing how the seeds sown by him and Dr. Geoffrey Robson, who was appointed to execute the vision and became the first Head of the Seismic Research Unit, had found such fertile ground at St. Augustine and had grown into a full-scale regional organisation. Although his mark on the wider seismological world is undeniable, for many years his Willmore seismographs were used in recording earthquakes in our region and he derived tremendous satisfaction from learning of the continued development of our agency as part of the legacy of his work. Limitations in the seismograph recording technology of that era and the dependence on the postal service meant that incipient unrest at any of the volcanoes could go unrecognised for several days, sometimes weeks, depending on postal schedules. In 1970, the first radio-linked seismographs (telemetry with VHF radios) were installed at Pointe-a-Pierre and Brigand Hill, Trinidad, to give real-time readout on pen recorders at the Unit, which could be regularly inspected. This was the introduction of real-time monitoring, which was a most significant development and is especially critical in the surveillance of live volcanoes. With time, telemetry was extended to eventually cover the entire network. Six drum recorders were on continuous display to allow real-time assessment of the activity occurring throughout the region. From the early 1970s, data for earthquake locations were recorded on a 24-channel, magnetic tape recording system, with a medical, ink-jet plotter for producing seismograms. This real-time upgrade was in place on Good Friday, 13th April, 1979, to capture the volcanic unrest that signalled the imminent eruption of the Soufrière volcano, St. Vincent. An unusually high level of seismic tremor at the stations located on the flanks of the volcano was noted in the late afternoon and the escalation tracked, in real-time, allowing the Prime Minister of St. Vincent to be alerted by 10pm, 12th April, that a volcanic crisis appeared to be developing. By dawn, the volcano was in full-scale eruption. Scientists and technicians from the Unit served several tours of duty at a temporary observatory position in St. Vincent for several months, until activity subsided.

Limitations in the seismograph recording technology of that era and the dependence on the postal service meant that incipient unrest at any of the volcanoes could go unrecognised for several days, sometimes weeks, depending on postal schedules. In 1970, the first radio-linked seismographs (telemetry with VHF radios) were installed at Pointe-a-Pierre and Brigand Hill, Trinidad, to give real-time readout on pen recorders at the Unit, which could be regularly inspected. This was the introduction of real-time monitoring, which was a most significant development and is especially critical in the surveillance of live volcanoes. With time, telemetry was extended to eventually cover the entire network. Six drum recorders were on continuous display to allow real-time assessment of the activity occurring throughout the region. From the early 1970s, data for earthquake locations were recorded on a 24-channel, magnetic tape recording system, with a medical, ink-jet plotter for producing seismograms. This real-time upgrade was in place on Good Friday, 13th April, 1979, to capture the volcanic unrest that signalled the imminent eruption of the Soufrière volcano, St. Vincent. An unusually high level of seismic tremor at the stations located on the flanks of the volcano was noted in the late afternoon and the escalation tracked, in real-time, allowing the Prime Minister of St. Vincent to be alerted by 10pm, 12th April, that a volcanic crisis appeared to be developing. By dawn, the volcano was in full-scale eruption. Scientists and technicians from the Unit served several tours of duty at a temporary observatory position in St. Vincent for several months, until activity subsided. The ability to predict the behaviour of a physical system governed by stated laws is the ultimate test of any scientific theory. Seismology is no different, and earthquake prediction has been described as the holy grail of seismology. It was also in 1982 that a novel earthquake-forecasting technique being explored by one of our scientists was tested, in real-time, on an escalating earthquake sequence in the vicinity of south-west Tobago. On the 17th September, civil authorities were advised that the analysis of the events suggested that the activity could lead to an earthquake of magnitude 5.0 or larger. In response to the advisory, response agencies were put on alert. The main shock of the sequence, with magnitude 5.2, occurred on 20th September. After a similar success with the technique in 1997, it has been further refined and tested on the global system and the San Andreas Fault zone for consideration by the seismological community.

The ability to predict the behaviour of a physical system governed by stated laws is the ultimate test of any scientific theory. Seismology is no different, and earthquake prediction has been described as the holy grail of seismology. It was also in 1982 that a novel earthquake-forecasting technique being explored by one of our scientists was tested, in real-time, on an escalating earthquake sequence in the vicinity of south-west Tobago. On the 17th September, civil authorities were advised that the analysis of the events suggested that the activity could lead to an earthquake of magnitude 5.0 or larger. In response to the advisory, response agencies were put on alert. The main shock of the sequence, with magnitude 5.2, occurred on 20th September. After a similar success with the technique in 1997, it has been further refined and tested on the global system and the San Andreas Fault zone for consideration by the seismological community. From the mid-1980s to the turn of the Century, due primarily to the economic climate, the Unit experienced the most volatile phase of staffing. There was a net overall decline in the total number of Staff until 1990, with a marked increase in the ratio of academic to non-academic positions, with the number of Staff (both academic and technical) at the lowest level in several years. As economic fortunes in the contributing territories reversed, staff positions were restored. It is important to note that in spite of the challenges during this period, Staff, scientific and non-academic, worked to ensure that while large scale upgrades were not possible, little ground was lost in our monitoring role. Staff commitment ensured that systems continued to improve, in spite of the constraints.

From the mid-1980s to the turn of the Century, due primarily to the economic climate, the Unit experienced the most volatile phase of staffing. There was a net overall decline in the total number of Staff until 1990, with a marked increase in the ratio of academic to non-academic positions, with the number of Staff (both academic and technical) at the lowest level in several years. As economic fortunes in the contributing territories reversed, staff positions were restored. It is important to note that in spite of the challenges during this period, Staff, scientific and non-academic, worked to ensure that while large scale upgrades were not possible, little ground was lost in our monitoring role. Staff commitment ensured that systems continued to improve, in spite of the constraints. The SRC of today has benefitted from the input of scientists from around the world and many of these former staff members, who helped to lay the foundation for the very important pursuit of earthquake and volcano monitoring and understanding of the processes at work in the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean have excelled internationally, but have continued to promote the work of the SRC whenever possible. At every stage, many who have joined the staff have quickly embraced our vision, and those who have put in long service have been the unbroken thread connecting back to the founders over the 60 years of our operations.

The SRC of today has benefitted from the input of scientists from around the world and many of these former staff members, who helped to lay the foundation for the very important pursuit of earthquake and volcano monitoring and understanding of the processes at work in the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean have excelled internationally, but have continued to promote the work of the SRC whenever possible. At every stage, many who have joined the staff have quickly embraced our vision, and those who have put in long service have been the unbroken thread connecting back to the founders over the 60 years of our operations.