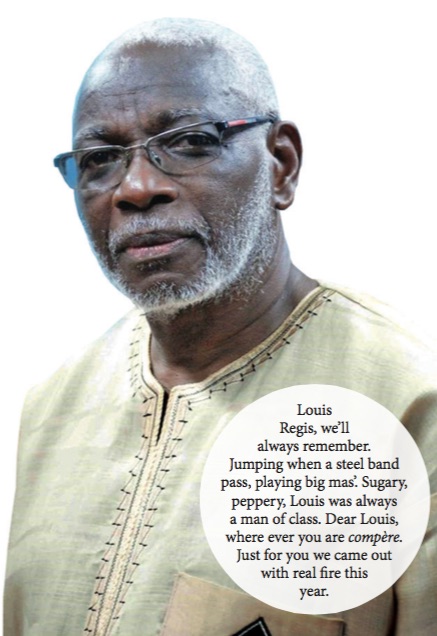

Dr Louis Regis, who passed away in December 2018, is fondly remembered as an inspiring teacher and leading expert on calypso. He was the author of numerous academic articles and several books. His three major titles are: Race, Ethnicity and Nationalism in the Trinidad and Tobago Calypso 1970-1998 (2017); Black Stalin: Kaisonian (2007); and The Political Calypso: True Opposition in Trinidad and Tobago (1998).

Dr Regis served as Senior Lecturer in Literatures in English and as the first Head of the Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and Education (FHE).

According to the Dean of FHE, Dr Heather Cateau, “Louis will be remembered for his deep and genuine love for our culture, especially calypso music. This love of our culture led to a mastery of his subject matter, which pervaded all aspects of his teaching and research. He helped change the ways in which our culture is integrated into our education system and his reach was keenly felt at the secondary and tertiary levels. We have lost a true maestro of our culture.”

Dr Louis Regis is missed deeply by his wife, Dr Ferne Louanne Regis, their children Kosi and Kaya, other family members, colleagues, friends, and students.

Every year somebody dear

Give us cause to shed a tear

And mourn for he is gone

Now all that’s left is a faint memory

Based on the theme of a strange melody

Still we must think of him

And recall his image with pride

Telling people from deep inside

This is dedicated to Louis who died

Adaptation of Sparrow’s Memories

UWI Today has included Dr Regis' short story The Readiness Is All.

James liked to believe that he was a philosopher. Standing outside the church where a funeral service was taking place he indulged in his private reflections. “A funeral has at least three centres,” he thought, “a church where the bereaved, the conventional and the curious congregate to sing ‘Blessed Assurance’; a churchyard lime where the idle, the irreverent and the irreligious assemble to ole talk; and lastly a grave, a yawning hole waiting to swallow up its unconscious tenant.”

Funerals always fascinated James. He marvelled at the fact that beneath superficial differences they all served the same function; they helped people deal with irrevocable loss. He didn’t think himself morbid but he had spent much time reflecting upon this aspect of life and yet each funeral made him revisit his theories, revise his notions of the nature of life and of the after-life something no amount of belief or disbelief had been able to sort out in his mind.

James often wondered if this preoccupation with funerals originated in his past. One lasting memory of his childhood was attending the funeral of YoYo, the family housekeeper. Too small to walk in procession to the cemetery, he had been driven there in the hearse conveying YoYo’s remains. After the hole was filled, James was handed over the grave several times. Later in life when he brought it up with his mother, a devout Roman Catholic, she never said anything leaving him to question if what he remembered was true in the first place.

Life in his home village gave him a peculiar two- dimensional vision of funerals. His childhood delight had long been replaced by an adolescent intolerance and he had grown to despise the long dusty processions of mourners, profusely powdered in cheap talc, stifling in cheap scent, sweltering in their black outfits. He found their dreary prayers and droning hymns too morbid for his young mind. He couldn’t bear the despairing wails and the hollow thud of the first handful of dirt on the coffin. What irked him most of all was the antics of those inveterate funeral goers who seemed to think that a funeral was entertainment; more often than not many of them never managed to make it past one or other of the many rum shops which the village possessed in curious disproportiontoitspopulation. To James this behaviour symbolised the backwardness of the village as a whole. And yet he conceded that there was something about village funerals that eluded him.

Life in his home village gave him a peculiar two-dimensional vision of funerals. His childhood delight had long been replaced by an adolescent intolerance and he had grown to despise the long dusty processions of mourners, profusely powdered in cheap talc, stifling in cheap scent, sweltering in their black outfits. He found their dreary prayers and droning hymns too morbid for his young mind. He couldn’t bear the despairing wails and the hollow thud of the first handful of dirt on the coffin. What irked him most of all was the antics of those inveterate funeral goers who seemed to think that a funeral was entertainment; more often than not many of them never managed to make it past one or other of the many rum shops which the village possessed in curious disproportion to its population. To James this behaviour symbolised the backwardness of the village as a whole. And yet he conceded that there was something about village funerals that eluded him.

One particular funeral scene lived on in his mind adding to his puzzlement about funerals in general.

The father of one of his friends, a member of the group which styled itself The Brethren, finally succumbed to alcohol and was being laid to rest with prayer and hymn. Despite the deceased’s want of religion and his son’s rejection of Christianity, the dead man was being churched. Neither father nor son could seriously object. A funeral service was the way of the village.

James usually avoided the deceased whose drunken antics caused him fear and wonderment as a child, but out of respect for the Brother, he arrayed himself in carefully-ironed soft shirt and new-brand blue jeans and passed an ineffectual comb through his large Afro. His mother watched him go, throwing behind him the provocative words, “Is so people does go funeral now?” James ignored her.

Baj’s grandfather, imposing in solid black, stood guard at the entrance of the church which was located next to the cemetery. Whenever an unkempt bejeaned youth, fresh from the blocks, filtered into the graveyard, his respectable frame registered disapproval and indignation. The youths, Baj included, simply walked past him and headed for the grave. This choice of centre mystified James. Normally a few individuals would go to inspect the hole and then withdraw satisfied that it was ready for its part in the drama, but on that day ragged youths lined the perimeter, lost in silent thought. James joined them in their unexplained vigil.

Curiosity finally got the better of Baj’s grandfather who had been eyeing the group all the while. He left his station and approached the gravesite. No one said anything; no one acknowledged his being there.

“Wha’ is dat?” he asked, pointing to some loose dirt which had rolled into the grave. No one answered.

“Who put it dey?” the luckless intruder continued.

“Baj,” replied Tall Boy laconically.

Sensing a hidden joke at his expense, Baj’s grandfather darted quick glances at the youths. They returned impassive faces, closed to him. He fled. No one watched him go, no one commented. All seemed locked into vibrations emanating from the open wound at their feet. James, who found the incident quite funny, gave up trying to interpret the mood of the Brethren and he drifted into his private thoughts. Someone nudged him. He started, accepted the proffered joint, took the standard drags and passed it on.

The cortege arrived hole-side and The Brethren dispersed. None of them ever mentioned the incident.

Then his own father died, a stranger to his wife, his children, his mistresses, his relatives, perhaps even to himself. James felt nothing. He viewed the funeral preparations with detached indifference. He took pains to arrive late for the funeral service to avoid being drawn into a family circle and having to be involved in the bacchanal which he heard that his aunt was hoping to stage in order to embarrass his mother. Reaching late as he had planned, he saw the poet and the playwright, each wrapped in an impenetrable soledad. The playwright paced the driveway obviously agitated about something which he characteristically saw no need to divulge in conversation; the poet excused his presence by alleging that he wanted to witness James’ reactions. James didn’t know how to humour him.

When the coffin was wheeled out of the church there occurred one of those incredible moments which James had experienced in different situations. He had seen his brothers escorting the corpse but all of them seem to have disappeared. He went over to gaze for the last time at the face which he hadn’t cared to see in life. Something kept him gazing and preoccupied with his own thoughts he didn’t see people filing out of the church. And then finally the meaning of funerals came home to him. Looking up he recognised a group of familiar faces. These people had departed from their Friday evening routines to do him respect. They had come out a sense of personal decency, their presence signalling that they accepted in him something that they valued in themselves. Perhaps that was the key to funerals. They weren’t about the dead but about the living affirming common humanity.

In a strange way, he was reminded of the desolation he had felt after a series of reunion performances which he had directed. On the last night, even while on stage, several of the performers were overcome by the sadness of farewell. Afterwards, watching performers, producers and patrons milling around in the foyer reluctant to tear themselves away from that moment, he was stricken with a sense of final loss. The disintegration of the brotherhood of the Brethren hadn’t struck him as forcefully because it had been a long imperceptible process, although painful at its most dramatic junctures. This abrupt leave-taking of this beautiful group who through the years had filled the void in his life caused him deep anguish.

Now greeting every one of those who had come to pay their respects to him, he felt a strong sense of comradeship with people with whom he hadn’t thought he had much in common. This is what funerals are about, he thought. Religions guarantee the hope of an after-life but funerals demonstrate life’s temporary victory over Death. Death can wear us down one by one but the coming together of the survivors signals that in the midst of death there is life. Those villagers of his youth knew this because they were in tune with the cycles of life. They knew that despite the ceremonial and the ritual and with all due deference to the grief of the bereaved a funeral is the ultimate lime.

Weeks later, he sat on a tomb watching the artist stride across a churchyard to come to rest on the same tomb, planting large feet on that part of the concrete slab which protected the head of the interred from precisely such violation of his rest. The poet sat a few feet away on the same tomb but gingerly so as not to offend the living. The lime formed itself and indulged in easy ole talk interspersed with ribald jest and raucous laughter. Later they checked in at a friendly bar. The artist raised his bottle.

“To life,” he declared in solemn toast.

“To life,” we chorused.

Louis Regis (1996)

Louis Regis, we'll always remember

Jumping when a steel band pass, playing big mas’

Sugary, peppery, Louis was always a man of class

Dear Louis, where ever you are compère

Just for you we came out with real fire this year