|

|

|

|

July 2009

|

Being the centre

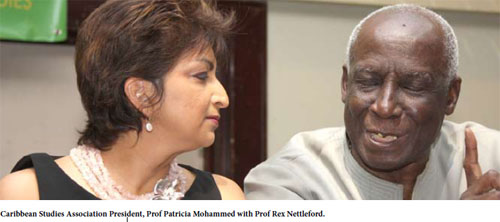

The theme, “Centering the Caribbean in Caribbean Studies,” conceptualized by Prof Patricia Mohammed and Dr Diana Thorburn, was itself a subject of hot debate as participants contested the multiplex definitions and identities of the phenomenon known as “the Caribbean.” That alone might indicate the complexity and depth of the 34th annual conference of the Caribbean Studies Association (CSA), which took place in Jamaica in June. In crafting the theme, Prof Mohammed’s concern was twofold: What contribution do successive conferences make to Caribbean societies and to what extent have these conferences captured the shifts and changing dynamics which Caribbean Studies have undergone in the last three decades? “The continued relevance of a framework for thinking about what is Caribbean Studies is not something that can be answered by others but by us—by those of us who live and breathe and work in the Caribbean dust and air, those of us who absorb this long distance and come in to take huge gulps and lungfuls,” she said at the conference, where she was named 2009 President. Commenting on the theme, PVC of Planning, Dr Bhoendradatt Tewarie, asked two questions. “What impact has the decades of Caribbean Studies had on the Caribbean? What has thinking, discussing and writing about the Caribbean done for the Caribbean?” The conference raised questions on whether traditional definitions of the Caribbean as a geographical entity in the United States’ backyard and multiple identities due to the historical experiences under British, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch colonialism still hold relevance or should be revisited. “There has to be a time when we come together unselfconsciously and with self-confidence to celebrate and endorse the condition of non-arrival for it is the fluidity of exchange and diversity of the region that will keep it alive and relevant to others and to ourselves. At the same time, it is about locating the centre of this process at the point from which Caribbean thought springs,” Prof Mohammed had earlier said. This assertion that it was time to invert an old process was not the only focus of the conference. CSA launched other important partnerships with the Inter-American Foundation, and the Organization of the American States. At the close of the OAS General Assembly in San Pedro, Honduras, OAS Assistant Secretary General, Ambassador Albert Ramdin, hurried to catch the last day of the CSA to host the plenary, “Centering the Caribbean in Western Hemispheric Relations,” which questioned what the region will look like in 20 years.

Graduate students were also a priority of the CSA organizers, with a Graduate Student Breakfast held at the Courtleigh Hotel where lecturers bonded, advised and nurtured graduate students. Another panel entitled “Finishing the Ph.D and Getting a Job,” was geared toward assisting PhD students to understand the process of completing their dissertation and preparing them for the job market. Caribbean scholars still need to respond to the piercing questions of what impact has the decades of Caribbean Studies had on the Caribbean and what has thinking, discussing and writing about the Caribbean done for the region. The answers may partly be found in defining and nderstanding the role of our academic institutions and the extent to which our intellectuals and scholars are engaged in independent and critical thought and action. Another useful exercise would be an assessment of whether the decades of Caribbean discourse have been translated into concrete policy and the real contributions it has made to the region. Perhaps the most challenging endeavour would be an evaluation of the extent to which personal interests, ego, ambition, corruption and petty politics in the academic, policy and political arenas have debilitated real progress and posed obstacles to the social, political and economic development of the region. |

The focus this year was also on adding to the mix of graduates from the United States and Europe and the participation of graduates from Cuba, Haiti, Suriname, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica and Barbados to allow them the opportunity to broaden their intellectual horizons and to network with their peers. Principal of the St Augustine Campus, Professor Clement Sankat, was particularly instrumental in this drive toward student engagement and facilitated the process through sponsorship of students to attend the event.

The focus this year was also on adding to the mix of graduates from the United States and Europe and the participation of graduates from Cuba, Haiti, Suriname, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica and Barbados to allow them the opportunity to broaden their intellectual horizons and to network with their peers. Principal of the St Augustine Campus, Professor Clement Sankat, was particularly instrumental in this drive toward student engagement and facilitated the process through sponsorship of students to attend the event.