|

July 2018

Issue Home >>

|

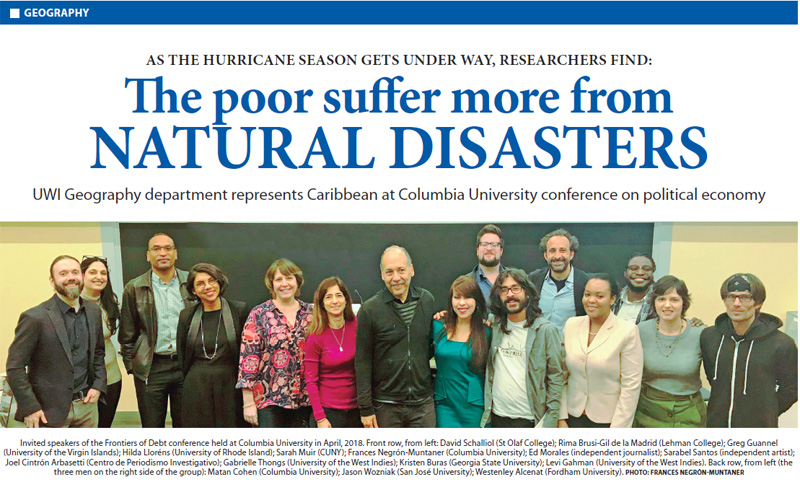

In late April, UWI Geographers Dr Gabrielle Thongs and Dr Levi Gahman were invited to Columbia University in New York to present their Caribbean-centred research on the nexus of disaster vulnerability, social inequality, colonial underdevelopment and global capitalism. The conference was held at the Columbia Law School and organized by the Unpayable Debt: Capital, Violence, and the New Global Economy working group of Columbia University’s Centre for the Study of Social Difference. The aim of the gathering was to bring together scholars, journalists, activists and artists to illustrate how new forms of extraction and debt are operating in the region, generating poverty and increasing risk.

Professor Sir Hilary Beckles, Vice-Chancellor of The UWI, delivered the opening keynote speech. He spoke of the historical damages caused by dispossession and slavery, current movements for global reparations, and the efforts of The UWI’s Centre for Reparation Research.

Dr Thongs spoke about factors that produce both social vulnerability and resilience as a way to determine the most effective disaster risk reduction strategies for the Caribbean. Dr Thongs said what were once predictable shifts in the wet and dry months are now erratic patterns of atmospheric tumult. She said there are more serious weather events, which demands more funding, resources, and labour to prevent escalations in damage and harm.

Pointing to widespread agreement based upon both meteorological data and lived experience, Dr Thongs said the Caribbean region’s seasons are changing, with consequences being increased coastal erosion, habitat devastation, wildlife loss, crop destruction, food import bills, and emotional distress. Rising sea levels, torrential rain, recurrent flooding and intensified hardships in the face of these things have become a “new normal,” she said.

One key finding offered by Dr Thongs’ combined society-environment approach is the significant role poverty plays in disaster survival. Her evidence showed that across the region, in most instances, hazard exposure may be relatively the same, but being poor drastically increases one’s exposure to a disaster and increases one’s potential harm.

Dr Thongs said impoverished people across region, to a disproportionate degree, must live in the most disaster-prone areas as these are appreciably cheaper than those of more protected backdrops. Such susceptible areas become more unsafe during and after extreme events because of how inaccessible they are for emergency service vehicles and first responders. Dr Thongs said impoverished people across region, to a disproportionate degree, must live in the most disaster-prone areas as these are appreciably cheaper than those of more protected backdrops. Such susceptible areas become more unsafe during and after extreme events because of how inaccessible they are for emergency service vehicles and first responders.

Dr Gahman gave an overview of how political structures and social orders, as well as certain cultural norms and economic relationships established via colonialism, are linked to and perpetuated by global capitalism and the state. Through an integrated focus on gender, class, race, and political ecology, Dr Gahman highlighted how debt, dependency, and vulnerability in the region are the products of imperialism.

To display the limitations of mainstream media accounts of disasters in the Caribbean, Gahman contended that what is often left often of the discussion regarding disaster narratives is the centuries-long, resiliency-eroding colonial extractions of the region’s resources and wealth, which could have otherwise been used to fund prevention and protection efforts for differing communities and ecosystems.

One present-day example he mentioned is how free trade policies, often including conditionalities of “adjustment” loans from institutions like the IMF, open the door for multinational corporations that undercut local businesses, siphon profits out of the region, and pollute the region more (most often in areas where poor communities live). He noted it is then not uncommon for people whose small businesses “fail” under this scheme, to later be heavily exploited inside the new foreign factories and hotels, where workplace abuse and sexual harassment occur more frequently.

Dr Gahman also detailed how social vulnerability is sustained and aggravated by state institutions and government ministries that continue to rely upon pre-independence administrative hierarchies and the logics of capitalism.

In linking these dynamics to “natural” disasters, Dr Gahman showed how women are exposed to more post-event contaminated water than anyone else, because they are generally tasked with performing unfair amounts of work related to care-taking, family hygiene, harvesting, cooking, cleaning, washing, and so on – a result of regressive notions about “women’s work” and inflexible gendered divisions of labour. He said women are further exposed to risk because of their lack of self-care due to their regular responsibility for the safety of children and the elderly. Women are also consistently the last to leave when disasters do strike, Gahman added.

Dr Thongs and Dr Gahman said their socio-geographical and political-ecological research reveals that in the Caribbean, risk, vulnerability, and the afflictions of disaster be they “natural,” debt, or austerity-related disasters), are:

- spatialized (i.e. arranged and ordered in particular and uncoincidental ways);

- overdetermined by both gender and race;

- lethally classist (i.e. on the whole, wealthier people can afford to live in safer places and live longer, consequently meaning poor people live in more hazardous areas and die sooner).

Thongs and Gahman ended by suggesting that more State support for work on poverty eradication, structural violence (defined as “exposure to premature death”), and slow violence (i.e. the chronic and seemingly imperceptible degradation of communities and ecosystems due to things like large-scale extraction, fossil fuel burning, deforestation, toxic dumping, and fallout from purportedly “natural” disasters) is vital for the wellbeing of all Caribbean societies and ecologies.

The two also said discernable university commitments to (and institutional backing for) research and teaching about disaster preparedness, gender equity, class consciousness, and development justice are necessary and urgent.

How is this “Geography”?

Geographers try to understand, explain, and sometimes even change, the processes and forces that shape and organize Earth. From the environmental and ecological to the cultural and social, geographers are concerned with contexts and connectedness, as well as influence and power. Geographers are forever preoccupied with why the world is arranged the way it is, how it is changing, and how relationships tie everything together – be they geophysical or geopolitical. The above work thus represents one small joint contribution to these broad efforts. Dr Thongs’ research on risk reduction demonstrates how disaster planning and spatial modeling can be used to reduce social vulnerability, while Dr Gahman’s work on development justice illustrates how colonialism, capitalism, and taken-for-granted gender norms continue to reverberate politically, materially, and even psychologically. Dr Gahman says: “Natural disasters are never immune to social, economic, and cultural forces and values, i.e. they are always political.”

|