Crawling under race ’s skin

The abrupt exit made by the students was distracting. It appeared to be a rude protest against the lecture taking place upstage at the LRC Lecture Auditorium. The lecturer was Dr Carlos Moore, Cuban-born ethnologist and political scientist. The topic was “Race and Culture in the Modern World.” The abrupt exit made by the students was distracting. It appeared to be a rude protest against the lecture taking place upstage at the LRC Lecture Auditorium. The lecturer was Dr Carlos Moore, Cuban-born ethnologist and political scientist. The topic was “Race and Culture in the Modern World.”

On a good day, surrounded by friends with your favourite drink at hand—on even such a good day—race can be a touchy issue. In a lecture theatre with students from different racial and ethnic groups, it can be an explosive topic. Moore, a former lecturer in the Institute of International Relations at The University of the West Indies (UWI), was on a dual purpose trip to Trinidad: to launch his memoir Pichon and give a public lecture on race and society.

He broke the ice by recounting his first memory of racial discrimination. As a child, a little white girl called him “pichon,” a word unknown to him, yet her tone conveyed the weight of its historic hatred. Later that day, his mother would make its meaning clear to him: a Spanish word meaning a nigger who eats dead flesh. Young Moore and other Caribbean folk like his family, who had migrated to Cuba for work, were nothing more than flesh-eating corbeaux.

Moore recalled how scarred he was by this and other slurs, and the intense racism that existed in a pre-Fidel Castro Cuba. It was this stratified society that led him to become a Marxist and an ardent supporter of La Revolucion.

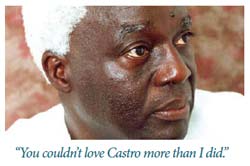

“You couldn’t love Castro more than I did,” he said.

But the Revolution did not bring a change in the status quo, and Moore realised that although the government had changed, racism was still very much alive in a Cuba that purported to be both race-less and class-less. Moore protested against Castro’s government, was imprisoned and soon found himself in exile in Egypt. His term of exile would last 34 years, during which, he spent time in Africa, South-East Asia and the South Pacific. He now lives in Brasil; and said it is a result of his nomadic nature that he speaks five languages fluently.

Within his first year in Egypt, Moore again encountered racism. Blithely greeting Egyptians he met on the street, he would only find out a year later—when he was more fluent in Arabic—that they too were tossing racial slurs at him and addressing him as a slave. This revelation set him to thinking about the history of race and he began to research an area that would become a life’s obsession.

Moore’s lecture challenged the way people tend to view and think about race. Many books have been written about race, he says, but few writers have probed the topic enough and they give the faulty impression that racism is a recent product of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Moore’s subsequent research dates racism back thousands of years. He cited information that pointed to a time as early as 1700 BC. He sees racism as a “pre-existing order” that was perpetuated by Arabs, Greeks, Romans and Sumerians. He also took an extended look into the invasion of the Middle East and other parts of Asia by the Aryans and its importance to the development of a Eurocentric notion of racial dominance.

His theories did not sit well with all members of the audience.

But his lecture and research didn’t rely only on historical data. Moore engaged the area of genetics to ground his argument. An obvious believer in evolution theory, Moore linked the beginnings of racism to the early human struggle for resources. Looking at the migration habits of early civilisations, he concluded that the formation of tribes stemmed from people sharing the same phenotype. They banded together, formed communities and shared their resources with each other. Tribes who differed in their phenotypic appearance would be viewed with suspicion. Resources were few during mankind’s hunter-gathering phase and tribes would try to lay claim to as much food as they could. Moore believes this struggle for one race to control the world’s resources continues even today. In the back of my mind, echoes of author, George Lipsitz, and former lecturer at UWI and African historian, Dr Fitzroy Baptiste came calling.

Moore believes that race is not an ideology as much as a historically created consciousness; and because of this, it is a permanent feature of our society. He went so far as to declare race a positive thing for those who use it, and negative only for those groups who are denied access to resources. According to him, this is why we need to challenge the issue and the way it is used.

From this train of thought he made the move to its contemporary uses and touched on the topic of the current President of the United States and what a Barack Obama presidency means for the world. His rise to power did not mean that racial prejudices no longer exist, but that they continue to be challenged.

Rhoda Bharath is a PhD research student in Cultural Studies. |