|

|

|

|

May 2009

|

This Is What We Believe In Essentially, to bring social movements from throughout the hemisphere together. Since 1998, social movements have used the opportunity of heads of government meeting, because there is so much attention focused on the heads, to have an alternative event. There’s a long tradition of social movements meeting simultaneously with official meetings. It gives the opportunity to interact, to share experiences to do current analyses of the situation: economic, social and political, depending on what the event is; and also to come together to put forward a common position which could then be communicated one way or the other to heads of government or institutions. This particular Peoples’ Summit was crucial because of the crises globally. We’ve focused a lot on the financial meltdown but that is just one dimension of what is really far more fundamental. It really is a crisis of the global capitalist system. Then there are the other crises: of environment, of energy, of food, of governance, and so on. We thought it would be a really important moment for social movements to discuss these, as we have been doing through the years, with the changing geo-political map of Latin America, with so many governments left of centre now being elected, and at the same time a new opening in the United States with Obama being elected, and not the very dogmatic ideological rigidity of a George Bush. All of those things combined to say that this IV Peoples’ Summit was going to be important.

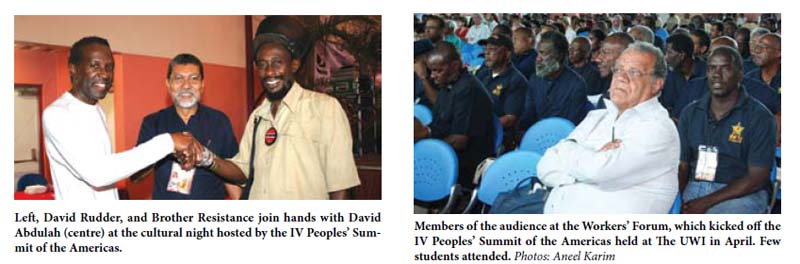

There was a comment at the closing plenary that it was a pity that we didn’t have more University students taking part in it. I think it was not great for UWI students because it was the week before exams. (Laughing) In my day, it wouldn’t have deterred us. Exams or no exams, we would have shown up. I know there were a lot of make-up lectures that week. There were some students, but not many. I think the University missed the opportunity of interacting. On the other hand, we did have some students who worked as volunteers, and that was positive. Some of them I think got very excited by what they heard and the people they met. We are hoping that we can keep some of those young people active and get them into the social movements and develop their awareness and consciousness. We also benefited from having a number of University professors and lecturers taking part actively. Prof Norman Girvan led a plenary, and Prof John Agard co-facilitated one and Prof Dennis Pantin facilitated another on energy sustainability. Dr Olabisi Kuboni facilitated a self-organised group on constitutional reform experiences in the Caribbean and Latin America, and Dr Wayne Kublalsingh facilitated one on resource protection, and there were others. If you reflect on your time as a UWI student and the environment you inhabited then on the campus, what do you see as the difference today? Social activism was much greater in my day (1972-1976). My first year I was treasurer of the Students’ Guild and in my second year I was its president. I continued to be very active even after. Social activism was clearly much greater. Over the last seven to eight years, there has been some attempt to reinvigorate social activism and consciousness. I know that because I have interacted with a number of young people who are trying to change campus politics. For example, there was a period in the nineties, and the early part of the century when Guild elections were being fought purely on party electoral lines, UNC/PNM, which also translated into ethnic politics. I got involved with some students, who were very unhappy about that type of thing, and they themselves had tried to contest and lost elections and they actually started a group called Students United Front which was a takeoff from the very group that we had on campus in the seventies. We started doing political education about the labour movement, of youth activism which goes back to the forties and fifties, about social movements and giving them a sense of history which they did not have. It was a complete awakening for them. The social activism is still very small. It is a process. Certainly the campus of today is not the campus of 35 years ago in terms of social activism and awareness of social issues. What implications are there for the region arising from the cluster of summits? As host country, Trinidad and Tobago, with Caricom’s agreement, should have put forward a clear set of policy proposals to deal with the global crisis, or hemispheric issues, and so on. We should have come to the table and said this is what we believe in, this is what we are advocating, this is what we are demanding, then the summit could have made sense. In that sense the labour movement failed, because we ought to have put forward our agenda to our governments before and agitated for that agenda beforehand and have people in our countries know that this is what we are doing. Given the recessionary climate, what recommendations would you make to alleviate suffering? There are some people who have argued for a social compact…interesting that nearly all of them, certainly the business groups and the politicians, are only calling for it now and they didn’t think of calling for it in the time of boom. We believe those who are calling for it now really want to use the social compact as an instrument of getting trade unions to agree to moderate our positions in terms of job security, in terms of collective bargaining, and so on. They now realise that they are in trouble and they want a way out. Before we come together to have a social compact, you have to have some kind of framework, an agreement in terms of what kind of society we wish to build. If we want to have a society dealing with equity and social justice, then employers’ associations, business groups, cannot condone their members violating the Minimum Wage Law or the Maternity Act. It has to mean that the Government cannot use Chinese or non-Caricom labour on projects when local labour is being shelved. Until we don’t change our position on those things, we can’t come to the table and talk. There are solutions, for example, to keep the employment level up, all the Chinese on those construction projects, if they are not there, that’s 2,000 more jobs in construction…If Government expenditure is taking place on infrastructure projects, then those projects as a matter of principle have to be given to local business people to enable taxpayers’ money to generate successive rounds of economic activity locally. The government cannot engage in mega projects like Rapid Rail, we have to say no to those because they are all going to be foreign content. We have to look at projects that impact on people’s lives. So let us look at making sure that in every community there are sidewalks for schoolchildren to walk to school safely on. Making sure the schools are properly repaired, that the health centres and the hospitals are okay, that all the recreational facilities are in place and properly maintained. These kinds of projects are what we need to be doing, micro not macro.

|