“Incubation lasted three days because this is how long the undergrad forgot the experiment in the fridge. #overlyhonestmethods”. Tweeted by a scientist with the trending hashtag started by a neuroscience postdoctoral researcher in January 2013.

It was meant to pull back the veil on some of hiccups behind scientific study.

There are some fields of work that we tend to imbue with an air of gravitas. Sciences are how we figure out the world around us; they use rigorous research to decipher the cogs that make the system work. It’s serious stuff. And sometimes nigh incomprehensible to the layman.

With #overlyhonestmethods, scientists spanning all fields detailed the simplistic and sometimes hilarious limitations to maintaining the scientific rigour we associate with research papers. One said of an experiment he had been working on that “the beam shutter was held stable by an in-house built support made from BluTak and the top of an old Biro.”

Whatever movies might have us think, scientists are not always functioning with limitless technology, funds, time or manpower. Especially when those scientists are students.

Sometimes a little ingenuity is necessary.

The presenters at the sixth annual research symposium, a collaboration between the Department of Life Sciences and the Departments of Physics and Computing and Information Technology at The UWI, put forward a myriad of thought-provoking studies. The two-day theme was ‘Sustainable Development,’ and most of the presentations looked at ways we can make improvements to the country and the region.

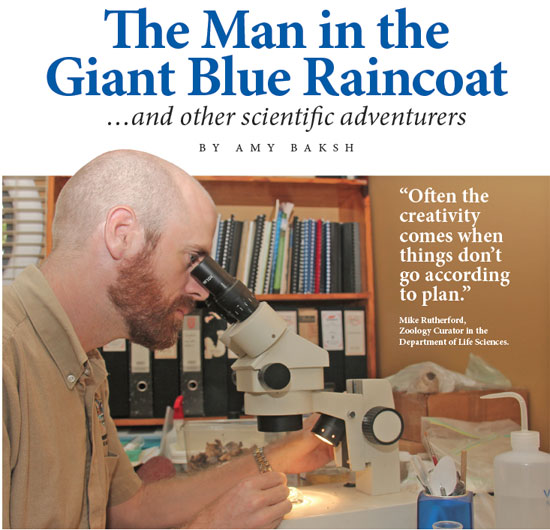

“Science is a very creative process. Not only do students have to come up with a question about a topic, they then have to figure out how to collect their data, how to analyse it and then compare it with what is already known,” says Mike Rutherford, Zoology Curator in the Department of Life Sciences. “Often the creativity comes when things don’t go according to plan… for example if you are in the field with a piece of equipment designed to do X and you discover that that is not working for your particular project, then you have to improvise and get the equipment to do Y instead. The other creative side is when you get results that might not have been a part of your original plan, and then find a way to use those results to answer different questions.”

Some of the conclusions were straightforward enough, like Marianna Rampaul’s assessment of Macqueripe Bay, where even a non-scientist could grasp the data showing high levels of E. Coli and Enterobacter in the water draining into the Bay (do not wash your feet in the drain water, I repeat, DO NOT wash your feet in that water). Some of the detailed charts and graphs, however, may have sailed over the heads of those not majoring in the field. Some of the conclusions were straightforward enough, like Marianna Rampaul’s assessment of Macqueripe Bay, where even a non-scientist could grasp the data showing high levels of E. Coli and Enterobacter in the water draining into the Bay (do not wash your feet in the drain water, I repeat, DO NOT wash your feet in that water). Some of the detailed charts and graphs, however, may have sailed over the heads of those not majoring in the field.

But most, if not all the presenters gave the audience a peek behind the glamour associated with scientific study. Keshan Mahabir, recounting his trips up to the Asa Wright Nature Centre to study the Oilbird population, showed pictures of how he got his data on population size: by standing on a precarious ladder in a giant blue raincoat, counting the birds in the cave with a flashlight.

Shaazia Salina Mohammed, when asked by one of the judges why she had chosen one type of perimeter in her study of Lionfish in Tobago rather than another, admitted rather bashfully that it was cheaper, and she was limited to the equipment available from the university.

And nothing wrong with that; she found ways to get the results she needed from the resources at hand.

There is no doubt that the students were rigorous in their research; and hopefully some of their work may soon be changing the way we live. Who wouldn’t rejoice at the introduction of year-round fresh pigeon peas, which might be on the market in the near future? Albertha Joseph-Alexander enthusiastically detailed the breeding of pigeon pea varieties that might be available for our collective currying soon.

Five years ago, she had written about her research on the link or genetic relationship between seed size, pod quality and yield in UWI TODAY (https://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/archive/june_2011/article6.asp).

But some of the most fascinating parts of the presentations were inevitably the parts of research that we don’t always consider. How do researchers make do with their limitations? Mike Rutherford’s look at mammals in the Arima Valley was professed to be just an investigation he found interesting, and he undertook it without quite knowing what he was looking for or what new information he might come upon. After detailing the animals he had spotted using cameras set up for the Arima Valley Bioblitz in 2013, Professor Christopher Starr helpfully suggested that he could have urinated on some of the sites to attract more animals. After all, that’s what the Prof. himself, a retired entomologist, had done in his own groundwork.

Well, whatever works.

Keshan Mahabir’s giant blue raincoat helped him get information that could garner attention to the dwindling Oilbirds up at Asa Wright, the only easily accessible colony of this strange, nocturnal species that doesn’t get as much good press as the flamboyant Scarlet Ibis.

Shaazia Salina Mohammed’s Lionfish study sheds light on the sea creature that has been creating panic since it was first spotted in Tobago’s waters, with many concerned that it could wreak havoc in Tobago’s coral reefs.

As the symposium grows, (having started off as solely Life Sciences to including Physics and Computing and IT) so does the span of research. Now even undergraduate students are given the stage to present alongside their postgrad colleagues and professional scientists. And even where data was limited by time, space or money, preliminary studies could pave the way for more transformative work.

However they get there.

Amy Baksh is a graduate of The UWI St. Augustine with a BA in History. |