|

November 2012

Issue Home >>

|

My mandate this morning is not to thank the University for this award, although I am very grateful, though apprehensive about the honour. My mandate from Principal Sankat is to speak to the graduating class for not more than ten minutes. Thanks be to God, no more than ten minutes. I want to begin with two sets of questions. My mandate this morning is not to thank the University for this award, although I am very grateful, though apprehensive about the honour. My mandate from Principal Sankat is to speak to the graduating class for not more than ten minutes. Thanks be to God, no more than ten minutes. I want to begin with two sets of questions.

Firstly, how many of you are human? Especially after three or four years at St. Augustine? How many of you have reflected long and deeply enough to be able to know whether the experience of university education has made you more or less human? How many of you, having looked at yourself at this stage of your lives, are clear that you are human, but have no intention of ever being humane?

The second set of questions is – how many of you consider yourselves citizens of your native or adopted land? Do you have a deeper and clearer sense of what such citizenship means at this stage of your tertiary education? How many of you have a committed sense of being a citizen because you have benefitted from free, subsidized or scholarship education? Do you have any sense of connection or obligation to the citizens and the state which made this education possible?

My young and not-so-young friends, I ask you, as you graduate this morning, to hold two words in your hearts and minds today and for the rest of your lives – HUMAN and CITIZEN. Are you a human being? Will you be a good citizen of Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, St. Lucia, and Dominica, a faithful son or daughter of the Caribbean?

To be human is more than a biological given. Some of you will have already experienced enough of the ecstasy or the pain of your bodily existence to know that you are more than your body. Three things distinguish us from other species: self-consciousness, choice and the moral imperative which flows from this, and our capacity for creative relationship with our environment, with the other and with the Transcendent. You who have studied the humanities ought to have developed a deeper consciousness of the complexity of being human, of the mysteriousness of every human being, especially as revealed through great literature, universal and West Indian. I hope that these studies have expanded your horizons in such a way that you will always stand in awe before the wonder of your own humanity and the humanity of others.

Yet we live in a reductionist world. Many of our human interactions are being commercialised. For years now, our leaders have betrayed us by throwing money at both our problems and our successes and hoping that that will suffice. I have never forgotten a line which I heard in a junior calypso contest several years ago, “If we don’t know how to go deep, deep, deep, we will never scale to de heights.”

Scaling to the heights invites us to have some common vision of what is best for us as human beings, of what qualities we expect in the best human being. The discourses about our socio-political life falter all the time because we have no agreement as to what we understand about human being, what our society should see as its fruit. Whenever I observe violent, disruptive behaviour on the streets or view it on the television, whether it happens in our underprivileged areas or in the hotspot to which Parliament itself is sometimes reduced, such behaviour in word or deed speaks of a lack of respect for self and for the other as well as deep wounds in individuals and groups which “Nuff Respect” does not heal. Violence and boisterousness trump reason and dialogue most times. Anger seems to become more and more acceptable in our relationships even when it leads to violence, even against our own children. Yet it is the very antithesis of full humanity.

Can the class of 2012 be the harbingers of a new humanity as you take your places in your families, in the workplace, and in the halls of power throughout the land? Can you be honest about your own dysfunctions so that you do not dump it on others in your search for recognition or acceptance? Such honesty draws us beyond self-consciousness to self-transcendence. For me as a Christian, it draws us to God in Christ. For others, to Brahman, to Allah, to Olodumare, to who or whatever we consider to be the ultimate source of our deepest fulfilment. BE HUMAN!

To be human must also mean to have a sense of humour. Archbishop Anthony Pantin of revered memory always used to say, “You can’t be a saint without a sense of humour.” I say to you, you can’t be human without a sense of humour. Especially, you have to be able to laugh at yourself.

When I went to tell the Archbishop that I had completed my undergraduate studies at UWI and was ready to move on, he said to me, “So now you have your BA? Remember that BA can mean Bachelor of Arts. Clyde, it can also mean Big A double S – and we all have the potential to be both.”

We both had a good laugh. He was one of my mentors. I could not resist the question, “Does that mean you do not want me to do my MA?” To which he replied, “It would have to be yours, not mine.” Be Human! Laugh at yourself often.

You are also called to be Citizens. The idea of citizenship takes us back to ancient Rome. A citizen was basically someone who was not a slave. In 1976, we said to the world that we wanted to be no longer subjects of a monarch, but rather citizens of a Republic. The French were very clear about the principles of the Republic, liberté, égalité, fraternité. I would like to translate that today as freedom, equality, community. My generation has tended to take these for granted as we wallowed in oil and gas. Your generation must see these as tasks yet to be achieved in law and in life. There can be no freedom without responsibility, no equality without justice and no community without respect. Even if achieved, none of that will endure unless there are citizens willing to promote and defend them. Archbishop Rowan Williams, soon to demit office as Archbishop of Canterbury, once said that “a good citizen has a good ‘nose,’ a certain instinct for the dishonest, the shabby, the evasive in public life.” The good citizen picks up the scent readily and acts in defence of freedom, equality and community.

How is your nose? Is it only about food, pleasure and self-interest? Or will you live your life responsibly, justly and with respect for all? If you are at all aware of the state of this nation, and I dare suggest of other islands as well, one of the daunting tasks awaiting you is to play your part as citizens in the restoration or reformation of every major institution in our society.

A word to the citizen-teachers who will enter the classrooms of the nation: We hope that you will be more deeply human and humane than the average citizen. Yours is the greatest burden for the future of our society. People love to speak about how bad, how difficult our young people are. They are just different. They are certainly different from my generation. I suspect that they are also different from you. See the mystery that is each one of them. Reverence them even as you seek to engage them.

Find in yourself the courage, the faithfulness, never to give up on anyone who is given to you as mentor and friend.

So, my dear graduates. Be Human. Be Citizen. Our country, this region needs human and humane citizens more than ever. I was a young St. Mary’s College student singing in the National Children’s choir at the Oval on the eve of Independence. Today, I look back on the past 50 years with gratitude for all the opportunities which this nation has given me, for the history which has shaped me; of which history this university has been an integral part. Fifty years from now, when Trinidad and Tobago celebrates its centenary, I pray that your own life experiences will enable you to know a similar sense of gratitude and deeper commitment.

There will be one big difference. It has been customary to say to graduates: The world awaits you. Today’s world is waiting for no one. The future comes at us faster than ever. The world is not waiting for you to develop or transform it. It will transform you even as it develops in ways beyond your imagining. May you be so deeply human, so engaged as a citizen that the transformation and development will be mutual. In such an experience, you will find your destiny and your joy. God bless you. I thank you.

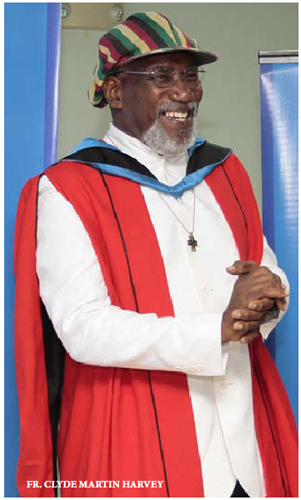

This address was delivered on October 27 to the graduating class of the Faculty of Humanities and Education.

|