|

November 2012

Issue Home >>

|

This is a historic moment for the Association of Commonwealth Universities. One hundred years ago, in 1912, the “Inaugural Congress of the Universities of the British Empire” was held in London. In an upcoming book, celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the ACU entitled “Universities for a New World” (edited by Professor Deryck Schreuder), Tamson Pietsch in his chapter entitled ‘the Universities Bureau and Congress of the Universities of the British empire (1913-1936),’ describes that 1912 Congress as a grand affair, where delegates who had travelled for weeks to get to Britain had a full programme of events, including tours to universities, dinners, lunch with the Prime Minister and other dignitaries and so on. Topics such as reciprocal recognition, teacher and student interchange, entrance requirements and remuneration were discussed. Reading all this was a source of some amusement because some of the same topics that exercised vice-chancellors and their academics at that time remain with us today. It was out of that Congress that a decision to form a Bureau was made, and in the next year, in January 1913, the Universities Bureau of the British Empire was established. It is this Bureau that is the predecessor of the Association of Commonwealth Universities and this meeting will kick off a year of celebration of the many contributions made over the past century to people of the Commonwealth by our organisation. This is a historic moment for the Association of Commonwealth Universities. One hundred years ago, in 1912, the “Inaugural Congress of the Universities of the British Empire” was held in London. In an upcoming book, celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the ACU entitled “Universities for a New World” (edited by Professor Deryck Schreuder), Tamson Pietsch in his chapter entitled ‘the Universities Bureau and Congress of the Universities of the British empire (1913-1936),’ describes that 1912 Congress as a grand affair, where delegates who had travelled for weeks to get to Britain had a full programme of events, including tours to universities, dinners, lunch with the Prime Minister and other dignitaries and so on. Topics such as reciprocal recognition, teacher and student interchange, entrance requirements and remuneration were discussed. Reading all this was a source of some amusement because some of the same topics that exercised vice-chancellors and their academics at that time remain with us today. It was out of that Congress that a decision to form a Bureau was made, and in the next year, in January 1913, the Universities Bureau of the British Empire was established. It is this Bureau that is the predecessor of the Association of Commonwealth Universities and this meeting will kick off a year of celebration of the many contributions made over the past century to people of the Commonwealth by our organisation.

That the ACU has survived the epochal changes of the last century is a considerable achievement. In addition to technological advancements, changes in life style and life expectancy, the last century has witnessed massive geopolitical shifts in power. It has been argued that the changes of the last century have been more profound than all of previous human history.

One important advance is that vast sectors of the world have gained access to education and we are riding the crest of a global revolution that aims to make primary and secondary education universal, and to enable entrance of a majority of these people into some form of post-secondary education.

In the English-speaking Caribbean, the first full-fledged university was established only in 1948 – it was this one, The University of the West Indies established here in Jamaica at this Mona site. In those early post World War II years, universities were also founded in many parts of Africa, India, Pakistan and South-east Asia in anticipation of the end of the British Empire. Those newly established universities, like their counterparts in the UK and industrialised dominions of the British Commonwealth catered only to a small elite.

Today, all that has changed. The rapid pace of technological advances in a globe dominated by the ethos of market capitalism and competition, in which competitive advantage is driven by knowledge creation and capacity has resulted in countries investing in new universities and the expansion of university enrolments and both have grown at an astounding rate. These circumstances have themselves changed the environment in which universities operate and the expectations of them. Governments, students and their families as well as the private sector and public in general are demanding programmes that are more aligned with workplace needs. Driven by hopes of advantage in commerce and the need for evidence-driven assistance in policy making, applied research is now favoured over more basic, abstract investigation. As competition for students has intensified, public relations and marketing departments are becoming as prevalent in publicly funded “not-for-profit” institutions as they are in their “for profit” competitors.

It is precisely in these circumstances that the theme of this Conference “University Rankings and Benchmarking: do they really matter?” becomes vitally important. Most of us are asking ourselves how we might better measure up to the needs of our stakeholders and indeed, what are the measures and deliverables that can best demonstrate value. The larger universities in more industrialised nations may count global ranking as a measure of their standing, but this does not necessarily answer the question of whether “true value” is provided to their communities. For the vast majority of universities, particularly in the developing world, the possibility of winning a place in the first 500 is unlikely, but they too must find some means of quantitatively assessing their own productivity, either by internally derived measures or by benchmarking themselves against other institutions nationally, regionally or globally. Our institutions are struggling to define productivity and value to their communities by measures that do not rely on publications in journals such as Science and Nature, or on assessments by peers from elite universities.

I hope this conference can provide us with new insights into these questions and that the ACU can build on these presentations to provide guidance in defining and measuring productivity in the diverse settings in which Commonwealth Universities operate.

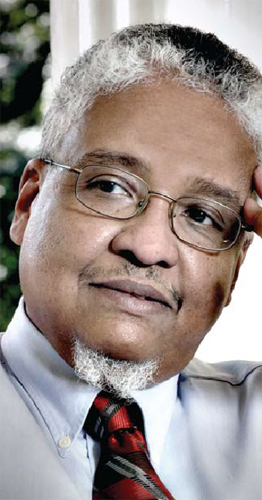

These remarks were made by Professor Nigel Harris, Vice Chancellor, The UWI at the opening ceremony of the Association of Commonwealth Universities 2012 Conference of Executive Heads at Mona, Kingston in November. |