|

September 2013

Issue Home >>

|

Twenty years ago, a man stumbled upon some remarkable documents in Cape Town, South Africa. The contents of these documents would signal the beginning of a 14-year, life-altering journey for Professor Charles P. Korr, as he worked to uncover the story behind a strictly FIFA-compliant, eight-club football league formed within the isolated confines of Robben Island prison, most famously known for Nelson Mandela’s 18-year incarceration there.

Now, I know what you might be thinking: A complex, well-organised football league in a prison? That’s preposterous!

It’s one of the oddest things you might expect to hear about a prison, especially one that housed political prisoners during South Africa’s era of apartheid.

But then I had the opportunity to sit down with Professor Korr at the Hyatt Regency hotel as he was visiting Trinidad to deliver a lecture. The result? My general apathy toward sports was startled into accepting that football is never just a game.

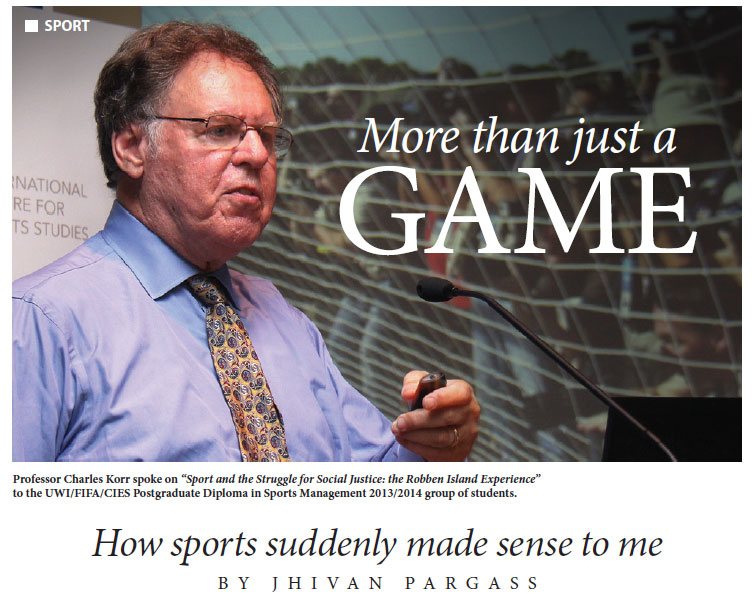

This was Professor Korr’s first visit to Trinidad. He was invited to deliver a special guest lecture to the UWI/FIFA/CIES Postgraduate Diploma in Sports Management 2013-2014 group of students, titled “Sport and the Struggle for Social Justice: the Robben Island Experience.” He gladly accepted, given his connection to the programme—a spinoff of the FIFA International Master in Law, Management and Humanities of Sport, in which he is visiting professor.

Comfortably seated at the Hyatt waterfront, Professor Korr began explaining the reason for his expansive research into this obscure discovery. It began when he was taken to the Robben Island archives, where he discovered something “bizarre,” the prisoners had been writing letters to each other during their time on the island, each closing with “Yours in sports,” a baffling touch when they were in such close proximity. Fascinated, he was eager to learn more, and subsequently found that the political prisoners had created a highly structured, highly bureaucratized football league during their incarceration. Digging deeper, he realised that the prisoners had compiled all the documentation you would expect from a premier league or the NBA. At that point, he knew he had to do something with the information. First came a feature film in 2007, “More Than Just a Game”, requested by FIFA’s Jerome Champagne, which Professor Korr co-produced. Two years later he co-authored a book by the same name, focusing on the stories of five former Robben Island prisoners, men with whom he has forged close friendships.

In the movies, Professor Korr said, the concept of sports in prison is always depicted as a mindless activity to take prisoners’ minds off their dreary existence. However, it was this same mundane essence of an everyday activity that, in part, made the Robben Island football league so extraordinary, considering the prisoners’ living conditions. He described the prison as “hell” where prisoners were forced to labour in a quarry, and had insufficient clothing, food and sleeping arrangements, coupled with a severe lack of contact with the outside world.

What I found fascinating is how football brought the prisoners together. There were two main political factions on the island: the African National Congress (ANC), and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), neither of whom agreed on anything—until it came to football. Being able to play football became important enough to submerge political differences on the island, and it took a collective effort of three and a half years to gain permission to play. Their persistence through various punitive measures, including the halving of meal rations, paid off, and the 1,400 prisoner-strong, eight-club Makana Football Association was established. The Makana F.A. is the only football association ever to be granted honorary FIFA membership.

At that moment, I had a moment of clarity. I understood the Robben Island experience; I suddenly knew why Professor Korr described football as “more than just a game.” The sport became a symbol of hope and freedom to the prisoners, and created a unified front in the struggle against apartheid. Football would never be the same for the prisoners again; they had showed they could beat the authorities. Just imagine, the chairman of the league was PAC, and the secretary ANC. The league’s constitution contained a “no discrimination” clause. One of the most poignant consequences was that the guards were forced to take the prisoners more seriously as people, no longer to be considered of a lesser race. They would eventually even challenge one another, place bets, and ask after the strongest players.

Professor Korr considers his Robben Island research to be “far and away, the best and most important thing [he’s] done, and ever will do as an academic.” He says that the acclaim achieved by the film and book brought an interesting transformation to his and the prisoners’ lives, adding that the book could best be described as demonstrating that “revolutions are made by foot soldiers, not generals”.

To put it plainly, my mind was blown.

Truthfully, sports had never held much interest for me. In preparation for the interview, I read for the first time about West Indian cricketer Sir Vivian Richards, unequivocally revered as one of the greatest batsman of all time. His determination in the 1970s, regarded as the darkest days of apartheid, led the West Indies cricket team to a 15-year stint of victory. He wanted to send a message that all cricketers were equal, and cricket thus took on much greater significance than a simple series of matches when politics was brought to the pitch. What I read forcefully resonated with me after hearing Professor Korr detail what the Robben Island prisoners achieved through football. I never knew sports could be so impactful.

As the interview wound down, I inquired as to the Professor’s impression of Trinidad thus far. He simply turned his head towards the sea and said, “that.” Living in the land-locked state of Missouri, thousands of miles from the coast, Trinidad’s waters carved his initial impression, as his first field-trip was to the beach. Incredibly, the last time he’d been on the beach was in 1970. He frowned at the timing of his arrival, which coincided with the one week of the year that the Asa Wright Nature Centre closes for maintenance, an unfortunate coincidence which prevented him from exploring Trinidad’s oldest nature centre. I thanked him for his time, and he departed, leaving me quietly to my racing thoughts, and my newfound respect for the game of football.

(http://us.macmillan.com/morethanjustagame/ChuckKorr has the book and here’s the IMDB link for the movie http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1144914/) |