Advances in DNA sequencing methods have helped law enforcement catch perpetrators and given rise to genealogy research whereby people learn more about their ancestry. But did you know researchers at the UWI St Augustine Cocoa Research Centre (CRC) are using DNA sequencing to offer a Cocoa DNA Fingerprinting service to help cultivators identify the variety and ancestry of cocoa they grow?

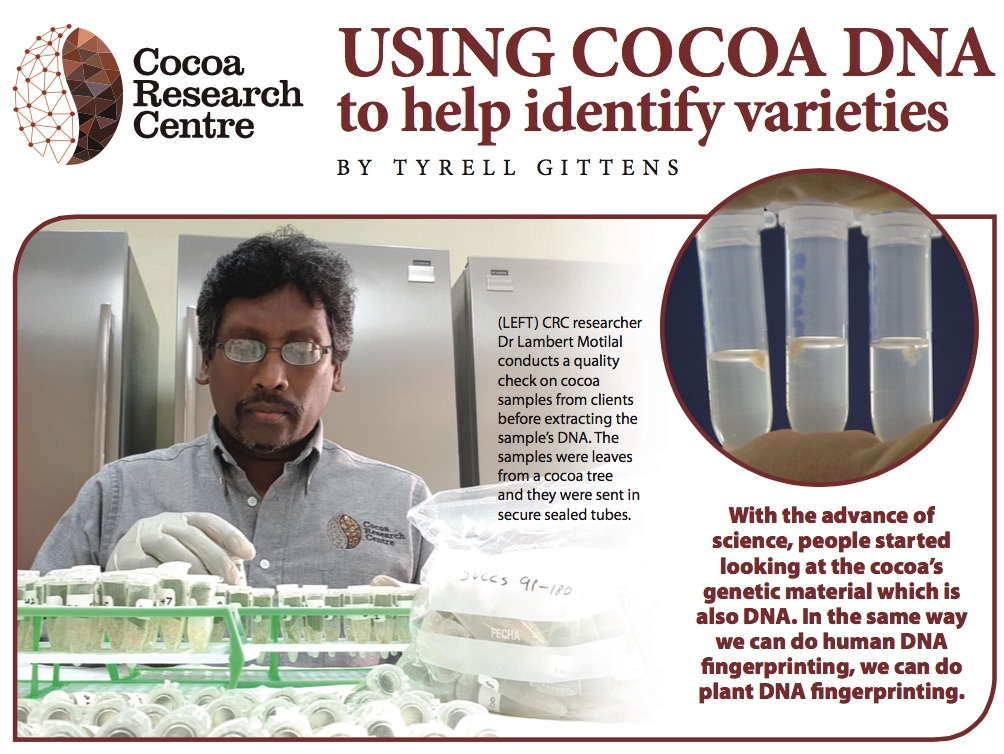

In an interview with UWI TODAY, CRC’s Team Leader of Genomics Dr Lambert Motilal said researchers once distinguished cocoa varieties using attributes like the colour of the tree’s leaves, size and shape of cocoa pods and beans, and the texture and taste of the cocoa pulp. However, these traditional methods were not very accurate and were susceptible to human errors.

“Using these sort of (traditional) descriptions to delineate varieties can only take us so far,” Dr Motilal explained.

“There is a DNA fingerprinting database for people where, if you are able to retrieve DNA from body tissue, you can determine if someone was present at a particular area by comparing their DNA profile to the profiles in the database,” he said. “With the advance of science, people started looking at the cocoa’s genetic material, which is also DNA. In the same way we can do human DNA fingerprinting, we can do plant DNA fingerprinting.”

Spearheaded by CRC director Prof Pathmanathan Umaharan – with assistance from Dr Motilal and other CRC researchers – the building blocks of the service were put together in 2015. In 2016, the centre started servicing its global clientele.

Several methods can be used to profile cocoa DNA, but the team at UWI uses single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and relies on the SNP profiles of over 2,300 cocoa varieties in the CRC curated International Cocoa Genebank Trinidad (ICGT) as its original DNA database.

“At CRC, we have developed a panel of SNP markers that will identify varieties in our genebank,” said Dr Motilal. “This panel can separate nearly all of them. The clients send us a leaf, or part of a leaf, and we extract the DNA from it and we use our panels of SNPs to fingerprint these samples that they sent.

“For example, we can tell if two varieties of cocoa are the same or if they are descended from a particular variety.”

Testing one sample costs US$51, and in 2020 alone, the CRC earned US$30,000. The service brought in US$38,000 in 2021.

Small batches of samples are sequenced at the centre, while large batches are outsourced to a facility which uses the CRC’s panels of SNPs. To date, the service has attracted clientele from Belize, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Ecuador, England, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Jamaica, Japan, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Taiwan, Thailand, Venezuela, and T&T. The CRC recently received service requests from the Philippines, Hawaii and Guyana.

Dr Motilal told UWI TODAY, “We decided to offer this service worldwide to anyone who wanted to determine what variety they had or find out its genetic background.”

He added, “Cocoa as a plant, like any other plant, has different varieties, including commercially improved farmer varieties, so some clients want to know what varieties they have.”

Clients often want to know if their samples share similar DNA to the ICS 1 and ICS 95 cocoa varieties which Motilal explained were naturally developed in T&T.

Researchers at The UWI’s previous incarnation – the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture – selected some varieties in Trinidad in the early 1930s and named the cocoa varieties “ICS”, which means Imperial College Selections.

Dr Motilal explained, “These two varieties were shared worldwide. There are ICS 1 varieties in the Caribbean, Indonesia, Pacific islands and in South America, for example. ICS 95 has great promise in terms of being partially resistant or tolerant to Frosty Pod Rot disease, which is a very impactful cocoa disease found in South and Central America but spreading through the Caribbean.”

As discussions continue about diversifying T&T’s economy, which will include expanding the local cocoa market, Dr Motilal said the CRC’s services are useful in many ways.

One way is helping farmers determine what varieties of cocoa are best to propagate and use, given that many local farms still have cocoa trees containing old genetic materials with high flavour profiles.

“We can tell the client their trees have certain ancestry profiles which gives a clue as to how the variety will progress and perform. A variety that is high in Amelonado ancestry is likely to have a strong cocoa flavour. A variety that is high in Criollo or Nacional ancestry is likely to have fine cocoa flavor,” he said.

While these services exist elsewhere, Motilal explained that investing in the centre’s services to ensure it remains cutting edge and a worldwide hub for science and technology can be financially lucrative:

“We would like The UWI to make this Cocoa DNA Fingerprinting service known locally, regionally and internationally.

“One way that we can make money for the university, one way we can keep ourselves afloat is to have consultancy services that people would actually like to have done with a reputable agency like the CRC.”