“I have always seen myself as a builder. This is that experience on a grander scale,” says Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, the new Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Campus Principal of The UWI St Augustine campus.

It’s been a few weeks since she officially assumed the position on August 1, and the time has been busy with “meetings, appearances and ascertaining the state of play on the campus,” she tells me. After our interview, she is scheduled to jet off to a ribbon-cutting ceremony. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

This is UWI TODAY’s third in-person interview with Professor Antoine, and an enormous workload has been a consistent feature in her professional life. She has successfully juggled senior roles all the way up to Dean of the Faculty of Law and Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the Board for Graduate Studies and Research. Apart from the occasional sigh and humorous aside, it doesn’t seem to phase her.

Yet some things have changed. In that first interview, she had just taken up the post of Dean at the new Faculty of Law on the St Augustine campus in 2014. Her office was a temporary space in the block of buildings that includes Chemistry labs and institutes. The second interview was in the spacious Dean’s office in the new Faculty of Law building. This time, she is in the ultimate office. In retrospect, her trajectory seems quite clear.

“I feel very honoured,” she says of being selected for the position. Her appointment was a unanimous decision, made by a 12-person panel made up of a cross-section of stakeholders. The media has also been in agreement with their choice, showing a strong consensus in favour of the appointment, and expressing optimism about what the campus can accomplish under her leadership.

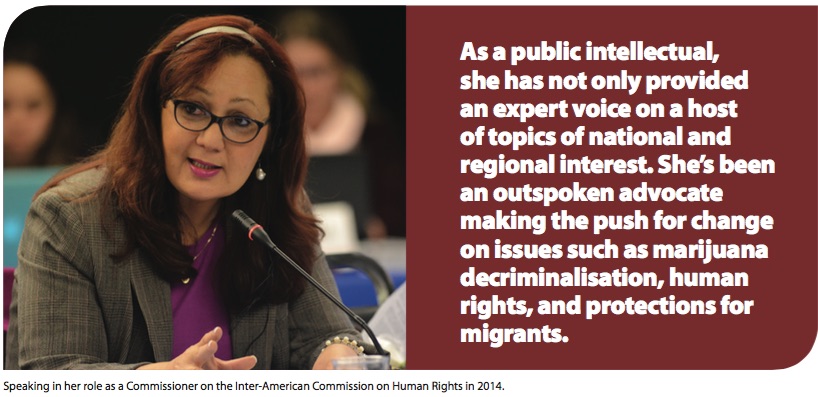

It makes sense. As a public intellectual she has not only provided an expert voice on a host of topics of national and regional interest, but also been an outspoken advocate making the push for change on issues such as marijuana decriminalisation, human rights, protections for migrants, as well as speaking on labour law issues and COVID-19. She has served as President of the Organisation of American States Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). At the IACHR, she also held the posts of Rapporteur for Persons of African Descent and Rapporteur for Indigenous Peoples.

In the course of her work she has won many awards. In 2022, she received the Caribbean Court of Justice’s Eminent Jurist Pioneering Woman Award. Her work in public service was recognised in 2013 with The UWI Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Excellence. It was her second win of this prestigious honour, the first being in 2006 for research.

“I can’t believe the outpouring of support and goodwill I have received,” she says.

However, while she’s grateful for the support, she is very conscious of the weight of the expectations placed upon her, and takes them very seriously.

“I don’t get excited easily,” she comments very pointedly. “I am aware of the enormous expectations placed upon me.”

If the expectations are grand, the challenges UWI St Augustine faces are massive. For several years now, the Government of Trinidad and Tobago (which provides a large amount of the university’s funding) has been cutting back on its investments in chunks. These last decades have also seen the rise of competing institutions of higher education, both in T&T and abroad. Long before the pandemic, the region had been dealing with slow economic growth. These negative forces have only intensified today, compounded by international conflicts and inflation. It’s an environment that may lead Caribbean society to weigh the value of higher education against other concerns. One could argue they’ve already been doing so.

The new Principal is very aware of difficulties.

“We have to take the good with the bad,” she says. “We may not have money to do all of what needs to be done, but if we are dynamic, driven, and work hard, and work as a team, we can do many things.”

She believes the current circumstances “give us a unique opportunity” to promote measures such as food security and sustainability – “Things we have a comparative advantage on.” As part of this push she intends on “greening” the campus.

So far, her work has involved “lots of listening”, she explains. One of her imperatives is re energising the campus community:

“I’m more focused on a new philosophy rather than new plans. I want to bring the magic back to UWI St Augustine. I want to bring back that sense of team, that dynamism. We need to reclaim the campus’s place in society. The intangibles matter. Once we do that, we will be more motivated to move on to bigger things.”

This isn’t surrendering concrete initiatives to carry the campus forward. On the contrary, the new Principal intends on implementing several plans that have stalled. Rationalising the institution’s programmes and services is a big priority.

She says, “There are many good plans that were not completed. I am known for my perseverance, and I strongly believe we should finish what we start.”

Indeed, during the regime of the previous Principal, Professor Brian Copeland, the campus did very good work in creating and sharing the vision for UWI St Augustine as a hub of innovation and entrepreneurship. She wants to ensure that the vision is concretised and realised.

Principal Antoine intends on going much further, and wants to “bring back campus social engagement”.

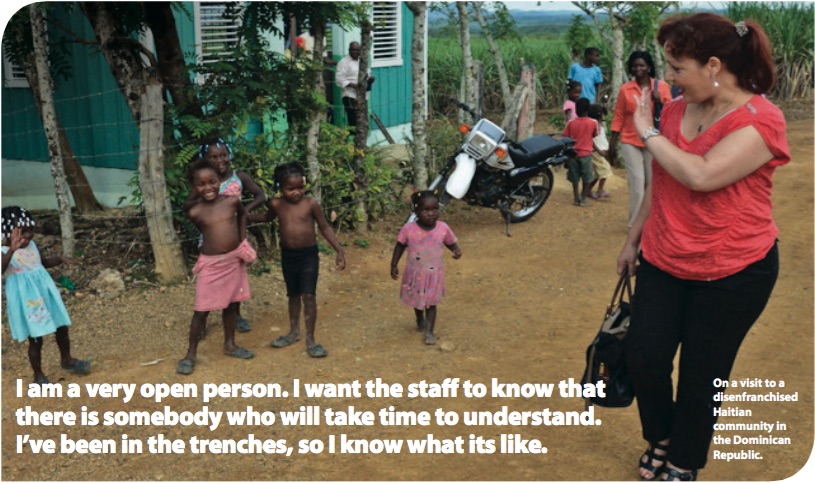

“There is a disconnect on the campus,” she says. “We are not together as a community. I would like to recapture that 'one mission, one goal’ energy. I am a very open person. I want the staff to know that there is somebody who will take time to understand. I’ve been in the trenches, so I know what it’s like.”

Improving the culture on the campus, she believes, will improve its services as a place of education and a regional resource for research, policy formulation, advocacy, and outreach. She speaks at length about the university’s role in Caribbean society.

“UWI is a vital institution. We must reclaim our role, not just as individual consultants and commentators, but as UWI St Augustine. I believe we have become less visible as an institution,” she says. And that has to change.

UWI St Augustine, she believes, is a special campus well-suited for the times:

“I see the St Augustine as unique in The UWI family. We are the only one with a Faculty of Agriculture, a Seismic Research Centre, and, until recently, a Faculty of Engineering. We are also close to Latin America and Guyana and can benefit from key partnerships with them.”

She hones in on climate change and food security as two areas of major importance in which UWI St Augustine should further intensify its efforts (the university is already making a considerable contribution, both as an institution and through several individual faculty, staff and even students). She is also very outspoken on the need for educational reform.

In a recent interview with Newsday, it was stated that “all [Professor Antoine’s] plans are in line with enhancing the quality of education, and at the same time ensuring everyone has access to tertiary education”. In our interview, she went even further, speaking on the need for greater educational access and equality in standards of education at all levels.

“It is a myth that we have free education in T&T,” she says. “It is also a myth that education is egalitarian. Poverty impacts educational outcomes. Location impacts outcomes. Home life impacts outcomes. Some students live in circumstances of poor and negative parenting. Some schools have no facilities or amenities. This situation affects people all over Trinidad and Tobago, especially those from poor and rural communities.”

She adds, “We have done a lot in education in T&T, but there is so much more we can do. If you say that the quality of education affects families, then you can see part of how we have come to be in such a negative cycle.”

Her views on education and giving opportunities to people who normally would not get a chance to receive a top educational experience led to the creation of the Makandal Daaga Scholarship. This Faculty of Law scholarship, named after the political activist and former revolutionary, was developed to “create lawyers who will be meaningful change agents within the Caribbean”. The first recipient, Kareem Marcelle (in 2017), is a young man from Sea Lots with an extraordinary ethic for community activism and social responsibility.

Kareem graduated with his Bachelor of Laws degree with honours, and is a dedicated public voice for the people of East Port-of-Spain.

Prof Antoine speaks of him with pride: “He proves that once you give someone an opportunity, they can move forward”.

The example of Kareem points to one of the new Principal’s greatest assets in her leadership role – experience. She’s done it before, and she’s succeeded.

“It feels like déjà vu,” she says of her first weeks in the new position. The parallels to the Faculty of Law, a brand new faculty during her time as the Dean, are numerous.

The position has required her to assemble a new team (this is still in progress), and create new systems. Most importantly, she has to build a culture to match her ambitions for the office. It sounds tedious, but when she describes what it was like the first time at the Faculty of Law, her eyes light up.

“It was a very valuable experience. I don’t regret one minute of it – teething pains and all. There were some rocky times, but I knew where I wanted us to go.”

In her eight years as Dean of the fledgling faculty, Law at UWI St Augustine expanded dramatically in a short space of time to hundreds of students (487 in academic year 2019/2020). Demand for placement in the faculty was much higher. Under her leadership, the faculty embraced modern and internationally relevant courses such as Banking Law, Oil and Gas Law, Sports Law, and Entertainment Law. Research and publication are flourishing. They even established the Faculty of Law’s International Human Rights Clinic and won important donor grants.

The UWI St Augustine Faculty of Law developed into a model for the kind of strong public presence that academia can achieve. Their well-established conferences and workshops received strong public support, including from the private sector.

“It was a good feeling,” she recalls. “I saw the fruits of our labour materialise.”

As with her current post, Principal Antoine paid close attention to the intangible aspects crucial for a high-functioning organisation. Indeed, despite the faculty’s many successes, she seems most proud of the culture they developed. The idea of law as a force for social good is one of her guiding principles, and it took hold among the staff and students.

She says, “It’s part of the faculty culture now. It tells me that we can harness people and we can change culture.”

Changing culture, however, is not easy. Still, she is not deterred, which may be her strongest asset of all: the confidence and determination to get it done.

“People sometimes ask me why I stay in the Caribbean, a question that surprises me sometimes,” she says. “I have faith in myself and I have faith in our people. I always measure myself against the best in the world. I always think big. When I look back, an important part of what I have achieved in my career is because I dared to think bigger.”

She is very much a regionalist. “I think of myself as Caribbean first,” she says. And that approach is reflected in her career. Regionalism will also, she says, be a big focus during her time as Campus Principal.

Professor Antoine’s work in the region is both extensive and transformative. She has served as lead consultant to all of the CARICOM governments (as well as to Canada, UK, USA, and numerous international organisations). She was the Chairperson of the CARICOM Regional Commission on Marijuana.

Her work in Caribbean Labour Law led her to author a 563-page report for proposed legislative amendments that has become recognised as the virtual bible for labour legislative reform and analysis in the region. She also led law reform efforts to successfully update labour laws in several Caribbean countries.

Principal Antoine acknowledges that, as a region, the odds are stacked against us, and there are double standards in international relations. Indeed, through her work she shaped the discourse on Offshore/International Financial Law, defending CARICOM governments and exposing these double standards from developed nations.

Nevertheless, through a positive attitude, self-belief, and a willingness to do the hard work, we can succeed.

She’s proved this in her own life, even from her days as a student at Cambridge and Oxford, where she was an outstanding scholar and author, and earned her doctorate in offshore financial law.

“Just as I went out there and proved what I could do, as a people, collectively, we need to do the same,” she says.

It’s that same confidence that guides her as a woman at the height of her profession.

“I never thought of myself in terms of gender like that,” she says. “I know the problems women face in these fields are very real. In fact, I’ve had to tell a gentleman or two in the past, ‘do you feel as though a woman should be seen and not heard?’ However, my father had no gender or racial biases.”

She laughs, “In my family, we understood that the women were the bosses.”

She does recognise that seeing her in this position can serve to inspire other women, and although not a font of advice on the topic, recommends to them that “if you have something to say or do, just say it, do it.”

It’s simple, straightforward and great advice for women, but also great advice for men, and great advice for an institution embarking on a new era.