SUNDAY 8TH MAY, 2016 – UWI TODAY

7

RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM

“Incubation lasted three days

because this is how

long the undergrad forgot the experiment in the fridge.

#overlyhonestmethods”. Tweeted by a scientist with the

trending hashtag started by a neuroscience postdoctoral

researcher in January 2013.

It was meant to pull back the veil on some of hiccups

behind scientific study.

There are some fields of work that we tend to imbue

with an air of gravitas. Sciences are how we figure out the

world around us; they use rigorous research to decipher

the cogs that make the system work. It’s serious stuff. And

sometimes nigh incomprehensible to the layman.

With #overlyhonestmethods, scientists spanning

all fields detailed the simplistic and sometimes hilarious

limitations to maintaining the scientific rigour we associate

with research papers. One said of an experiment he had

been working on that “the beam shutter was held stable by

an in-house built support made from BluTak and the top

of an old Biro.”

Whatever movies might have us think, scientists are not

always functioning with limitless technology, funds, time

or manpower. Especially when those scientists are students.

Sometimes a little ingenuity is necessary.

The presenters at the sixth annual research symposium,

a collaboration between the Department of Life Sciences

and the Departments of Physics and Computing and

Information Technology atThe UWI, put forward a myriad

of thought-provoking studies. The two-day theme was

‘Sustainable Development,’ and most of the presentations

looked at ways we can make improvements to the country

and the region.

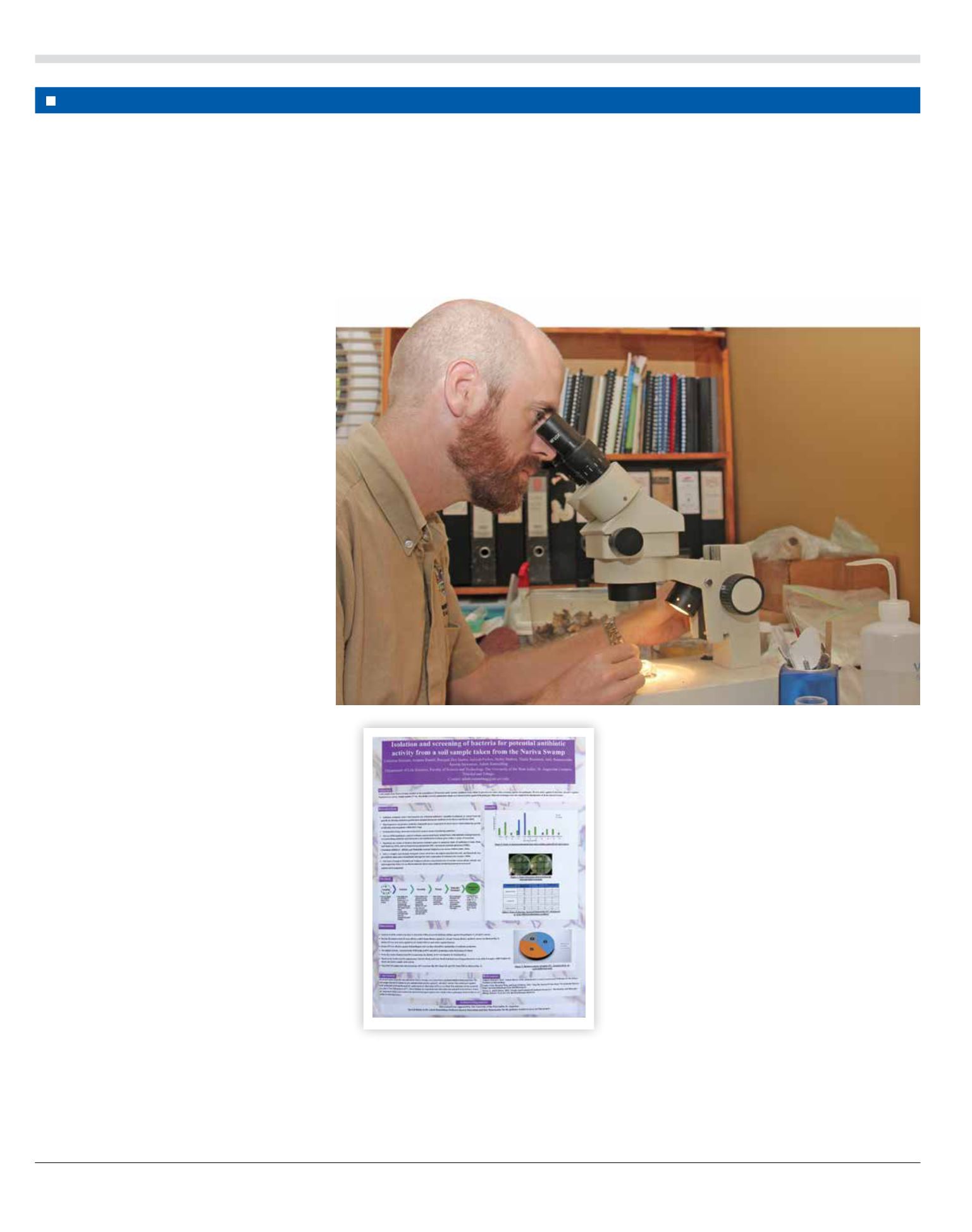

“Science is a very creative process. Not only do students

have to come up with a question about a topic, they then

have to figure out how to collect their data, how to analyse

it and then compare it with what is already known,” says

Mike Rutherford, Zoology Curator in the Department of

Life Sciences. “Often the creativity comes when things

don’t go according to plan… for example if you are in the

field with a piece of equipment designed to do X and you

discover that that is not working for your particular project,

then you have to improvise and get the equipment to do Y

instead. The other creative side is when you get results that

might not have been a part of your original plan, and then

find a way to use those results to answer different questions.”

Some of the conclusions were straightforward enough,

like Marianna Rampaul’s assessment of Macqueripe Bay,

where even a non-scientist could grasp the data showing

high levels of E. Coli and Enterobacter in the water draining

into the Bay (do not wash your feet in the drain water, I

repeat, DO NOT wash your feet in that water). Some of the

detailed charts and graphs, however, may have sailed over

the heads of those not majoring in the field.

But most, if not all the presenters gave the audience a

peek behind the glamour associated with scientific study.

Keshan Mahabir, recounting his trips up to the Asa Wright

Nature Centre to study the Oilbird population, showed

pictures of how he got his data on population size: by

standing on a precarious ladder in a giant blue raincoat,

counting the birds in the cave with a flashlight.

Shaazia Salina Mohammed, when asked by one of the

judges why she had chosen one type of perimeter in her

study of Lionfish in Tobago rather than another, admitted

rather bashfully that it was cheaper, and she was limited to

the equipment available from the university.

And nothing wrong with that; she found ways to get the

results she needed from the resources at hand.

There is no doubt that the students were rigorous in

their research; and hopefully some of their work may soon

be changing the way we live. Who wouldn’t rejoice at the

introduction of year-round fresh pigeon peas, which might

be on the market in the near future? Albertha Joseph-

Alexander enthusiastically detailed the breeding of pigeon

pea varieties that might be available for our collective

currying soon.

One of the posters on display at the symposium looking

for potential antibiotic activity at Nariva Swamp.

The Man in the

Giant Blue Raincoat

…and other scientific adventurers

B Y A M Y B A K S H

Amy Baksh is a graduate of The UWI St. Augustine with a BA in History.

Five years ago, she hadwritten about her research on the

link or genetic relationship between seed size, pod quality

and yield in UWI TODAY

/

archive/june_2011/article6.asp).

But some of the most fascinating parts of the

presentations were inevitably the parts of research that we

don’t always consider. How do researchers make do with

their limitations? Mike Rutherford’s look at mammals in

the Arima Valley was professed to be just an investigation

he found interesting, and he undertook it without quite

knowing what he was looking for or what new information

he might come upon. After detailing the animals he had

spotted using cameras set up for the Arima Valley Bioblitz

in 2013, Professor Christopher Starr helpfully suggested that

he could have urinated on some of the sites to attract more

animals. After all, that’s what the Prof. himself, a retired

entomologist, had done in his own groundwork.

Well, whatever works.

Keshan Mahabir’s giant blue raincoat helped him get

information that could garner attention to the dwindling

Oilbirds up at Asa Wright, the only easily accessible colony

of this strange, nocturnal species that doesn’t get as much

good press as the flamboyant Scarlet Ibis.

Shaazia Salina Mohammed’s Lionfish study sheds light

on the sea creature that has been creating panic since it was

first spotted in Tobago’s waters, with many concerned that

it could wreak havoc in Tobago’s coral reefs.

As the symposium grows, (having started off as solely

Life Sciences to including Physics and Computing and IT)

so does the span of research. Now even undergraduate

students are given the stage to present alongside their

postgrad colleagues and professional scientists. And even

where data was limited by time, space or money, preliminary

studies could pave the way for more transformative work.

However they get there.

“Often the

creativity

comes when

things don’t

go according

to plan.”

Mike Rutherford,

Zoology Curator in the

Department of Life Sciences.