Barbara Jenkins is protesting too much. “I didn’t set out to be a writer,” she says, seated in the garden of her Diego Martin home on a sunny afternoon with a cup of Earl Grey tea in her hand. “This is accidental.”

The “this” that Jenkins, a retired secondary school geography teacher, is so casually referring to is the remarkable success she has been enjoying since becoming a writer of fiction, five short years ago. She has won plaudits and prizes – including the Commonwealth Short Story Competition prize for the Caribbean region, two years running – and completed a Masters in Fine Arts (graduating with high commendation) at the St. Augustine Campus of UWI. Soon, her first book will be published through Peepal Tree Press in the UK. Titled Sic Transit Wagon, the book – which, in another form, was Jenkins’s MFA thesis – is a collection of 12 short stories inspired by contemporary life, as well as the world of pre-Independence Trinidad and Tobago. They’re written with skill, honesty and humour, and the wisdom they contain reflects a lifetime’s accumulation of varied, deeply felt experiences.

This late-in-the-day life as a writer began, as Jenkins would modestly have it, quite by chance. Back in 2007 a British friend was in the country for an extended period of time and wished to start a writing group. She invited one of Jenkins’ other friends to join, who would only go along if Jenkins accompanied her.

“We’d meet once a month or more often. You had to write something that could stand up to people’s criticism.”

The first major piece of writing Jenkins did for the group came out of a personal experience, one that many Trinidadians could unhappily relate to – vehicular traffic.

“I was going to UWI to a dyslexia conference. It took me an hour to do a hundred yards,” she recalls. “I said I’m not going and came back home after two hours. Since we were meeting that evening and I had nothing prepared I wrote a piece called 120 Minutes in Vision 2020, which was the big thing at the time. The group loved it. They laughed a lot at my predicament and about the situation and said, ‘You really ought to show this to somebody, you know.’”

That somebody was Nicholas Laughlin, editor of The Caribbean Review of Books. He liked it, and encouraged Jenkins to apply to the workshop for regional writers hosted by the Cropper Foundation. She did, and was accepted. “And when I got there and I saw that everybody was under 30, I kind of felt, Oh, OK, I’m twice their age, and when you hear the things they’d done, those who’d been writing their own blog for years and had published here, there and everywhere, I did feel a little bit inadequate.”

The experience did, however, show Jenkins that writing was possible not just as “frivolous enjoyment”, but something more. This led to her decision to do the MFA in Creative Writing at UWI.

“I go into things without thinking about them,” says Jenkins breezily, “and the MFA is one of those things. Without finding out anything about it, I boldly went up to UWI, paid fees and registered for it.”

Returning to a university campus after so many years was quite an experience for Jenkins, a mother of three children and a grandmother of six. Returning to a university campus after so many years was quite an experience for Jenkins, a mother of three children and a grandmother of six.

“I was at university in Wales in the early Sixties. The university environment then was an entirely different animal from what it is now.”

Whatever the differences, however, she found the UWI experience to be a “tremendous” one.

“The teachers at UWI, the ones that I’ve been exposed to, I don’t think I could have met better people anywhere,” she says. “ Thoroughly into their subjects, and well aware of a lot of stuff outside of their subject area. I fell in love with Professor [Barbara] Lalla, she was a great introduction. Vijay Maharaj, Maarit Forde and Gabrielle Hezekiah were great, too.

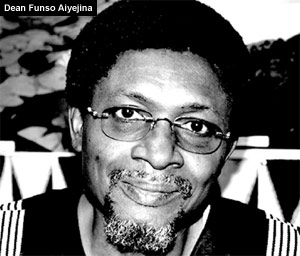

“But best of all was the friendship that I forged with my supervisor, Professor Funso Aiyejina – a kind friend and massive encourager but ferocious critic of my work.”

Still, she felt the MFA fell short of helping her acquire the tools with which to analyse the written word. She had gone into the degree expecting to be given “a training in creative writing”, but admits: “UWI did not, does not, do that, the nuts and bolts. It came as something of a surprise to me that the course was not teaching people writing, word by word, sentence by sentence.”

Instead she did classes in literary and cultural theory, optional courses in gender studies, and something called poetics. She feels that “There should be more courses, and more courses to do with the craft of writing.”

Overall, did she find the degree useful?

“Useful?” She pauses. “I don’t know about the utility of things, but I tell you, it was a fantastic ride. I loved every single minute. It was all stuff I had never been exposed to. I’m 70 years old and here I am saying my God, Aimé Cesairé, how come I never met this man before?”

Blame Jenkins’ ignorance of the great Martiniquan and other Caribbean writers on her sound colonial education.

“Caribbean literature did not exist when I was growing up; certainly not for the public library in Belmont.”

Belmont – the Port-of-Spain neighbourhood that has been the nurturing ground of so many of the country’s artistic and creative minds – was where Jenkins spent her childhood. Growing up in modest circumstances, there were no books in the house. “There wasn’t even a newspaper,” she says. “Not because we were philistines, but because, why you going to buy a newspaper when you could buy a hops bread?”

It was the free public library on Pelham Street, where Jenkins lived, that was to be the place where she would discover the joys of reading.

“It was always Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, the Just William series and, when I got older, PG Wodehouse and so on. Borrow two in the morning, and by two o’clock I’ve finished with both of them. And I’d go down to the library and the woman would say ‘No, you’ve had your two for the day already. Come back tomorrow morning.’ I’d be waiting outside when she opened the place at eight o’ clock to exchange my two for another two to devour.” “It was always Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, the Just William series and, when I got older, PG Wodehouse and so on. Borrow two in the morning, and by two o’clock I’ve finished with both of them. And I’d go down to the library and the woman would say ‘No, you’ve had your two for the day already. Come back tomorrow morning.’ I’d be waiting outside when she opened the place at eight o’ clock to exchange my two for another two to devour.”

Jenkins’s introduction to Caribbean literature came in the fifth form of St Joseph’s Convent, Port-of-Spain, courtesy of an Irish nun.

“She came into the classroom one day saying she had just come from St Lucia and she had been reading the work of a marvellous young man who was writing poetry, and she read us something from Derek Walcott’s 25 Poems.” Jenkins almost goes into a reverie at the memory.

“And there was something about Choiseul, and coming ‘round the bay, and the headland, and it was miraculous to think that what we had was worthy of being put into words and immortalised in print with a kind of a validity that we only gave to Tennyson and Wordsworth and stuff like that.” Despite being much more versed in Caribbean literature now – indeed, able to count Caribbean writers as her peers and some of them as friends – Jenkins declares that “my most enduring read is still Walcott.”

Jenkins credits her late husband with keeping her love of literature alive during her years as a geography teacher. “I was very, very lucky Paul recognised that I had this appetite that needed to be fed. I was at school all day, had to see about the family in the evenings, but I wouldn’t settle down at night unless I had read something.

“So he would buy books, particularly collections of short stories. (You just didn’t have time for the long haul of a novel. By the time you picked back up East of Eden you’d forgotten the characters.) I’d read a story and then I’d feel as if I had had, not escape really, but a life other than life. I didn’t know then how important it was.”

She became partial to women writers, especially Alice Munro, the doyenne of the short story. But she admits that “a man for all seasons for me is Graham Greene. Maybe he’s not very much in favour these days, but I love the way he was able to get to the heart of people’s motivations for doing things, no matter how base the motivation.”

Now that she is a writer herself, getting to the heart of the matter (as Greene might have put it) is what Jenkins tries to do herself, whether she’s writing about a long-time smartman trying to trick his way into bringing out a Carnival band, or a gaggle of modern, middle-class women gossiping over thegoings-on in their neighbourhood.

“I think through writing you’re forced to think more deeply about things and not just have things wash over you,” Jenkins observes. And as her writing career kicks into high gear, she doesn’t seem worried about what most writers would consider their greatest fear: running out of material.

“Life gives you a lot of traffic opportunities to write about.”

|